My ontological learning and coaching journey

In April 2021, I have started my ontological learning and coaching journey with The Coach Partnership (formerly Newfield Asia). On this page, I included some posts and videos in which I discuss what I have been learning in this journey.

7 November 2022

Kegan’s Theory of Adult Development

Some time ago I wrote about Robert Kegan’s stages of adult human development, a concept that I find really helpful when interpreting other people’s behavior. What is more, knowing about Kegan’s stages can be very impactful in helping us to grow as a person. While revisiting the concept this week, I discovered how difficult it is to achieve the last stage on Kegan’s “ladder”.

Let’s first start with a brief summary of the five stages, as described on this excellent page:

Stage 1 – the Impulsive mind, the stage in which we start out as young children.

Stage 2 – the Imperial mind. This is the stage that humans inhabit as adolescents. We are mainly concerned with ourselves. The purpose of our relationships and actions is to satisfy our own needs and interests. The most important motivators are external rewards and punishments. Interestingly, around 6% of people remain in this stage during adulthood. I believe that everyone knows an adult who is “stuck” in this stage.

Stage 3 – the Socialized mind. As the name suggests, our values, decisions and actions are primarily influenced by other people (family and friends) and the environment (societal norms, cultural customs, social media). We are very conscious about how others experience us and we mainly look for external validation. 58% of adults are in the socialized stage.

Some people can be very happy in this stage. But there are some obvious problems associated with this stage: a competitive mindset, which sets us up for perceived failure and disappointment, and not being focussed on what actually is good for ourselves. With a socialized mindset, we also experience confusion and stress when conflicting messages from our environment arrive and we try to satisfy everyone’s expectation (take for example conflicting messages from our spouse and boss about how we should allocate our time).

Another problem with the socialized mindset is that we tend to define ourselves by the results we get. However, it is important to remember that our results are determined by various factors, many of which are out of our control. And defining ourselves by our results completely ignores the fact that we constantly grow and develop, and that failure is the most important prerequisite for success. For instance, a runner with a poor Personal Best time can be a more serious runner than someone who can run much faster. The slower runner may be more dedicated and focussed on improvement. This is difficult to recognize if we only evaluate someone based on his or her performance.

Stage 4 — the Self-Authoring mind. In this stage, we follow our own course and do what we feel is best for us. Only 35% of the adult population are at this stage, which sometimes seems like an overestimate to me. I have realized is that I really enjoy the company of self-authorizing people, as the mindset of a person affects the content and character of a conversation. Socialized people tend to talk about their social environment, whereas self-authorizing people often talk about their own opinions, thoughts and goals, which is a lot more meaningful.

Stage 5 — The Self-Transforming mind, the highest stage on Kegan’s adult development ladder, which only 1% of the adult population inhabit. While in the self-authoring stage we question the outside world (the social environment), in the self-transforming stage we question ourselves. We are able to adapt to changing circumstances by transforming ourselves.

I previously have not reflected much on my ability to be self-transforming. But one example that suggests that I am still a long way from achieving this stage is the transition from in-person to online teaching at the onset of the COVID pandemic. I initially refused to accept that online teaching could work and conducted classes in person as long as possible, even though this constituted significant difficulties for the students and administrative staff. After finally being forced to change my teaching mode, I came to realize that online teaching can be very engaging and fun when making appropriate changes. However, if I had a self-transforming mindset, I would have voluntarily adopted online teaching and viewed the transition as a challenge and an opportunity to learn and innovate.

In the self-transforming stage, we can also understand things from many different perspectives. We realize that life and people are complex, and we can hold multiple opinions at once. For instance, if I do not agree with the philosophy and motivation of a colleague, I can consider reasons why the other person thinks differently and still engage in a productive collaboration, even if I don’t share the same values. Sadly, I find doing this rather difficult.

The realization that I am a long way from adopting a self-transforming mindset prompted the obvious question:

Why is it so difficult for me to achieve this stage?

What came to my mind is firstly that I wrongly believe that “I am my values”, when in fact “I am my actions”. Other people do not care whether what I do is based on some personal belief or philosophy. They only see and judge my actions. Hence, it would be wiser to let my actions tell people that I am someone who can adopt and be cooperative and helpful towards others.

The other major impediment to be self-transforming is my “be right” mindset. What I mean by that is that I am preoccupied with whether things that people do are right based on my own standards. If I assess that someone’s behavior, attitude or actions are not “right”, I find it very difficult to initiate cooperation and collaboration. This mindset is not helpful, because what matters is not to be right, but to obtain the results we want to achieve.

The next question is of course how to overcome these obstacles in my mindset, but I will leave this for another reflection.

20 May 2021

What is ontological learning and coaching and The Four Body Dispositions

20 May 2021

What is ontological learning and coaching and The Four Body Dispositions

20 May 2021

How to choose our mood and emotions intentionally?

One of the greatest insights I obtained from my coaching training was learning about Robert Kegan’s mental lenses of adult human development (as described HERE). According to Kegan, how we view things and make decisions in our lives actually changes during adulthood (or at least CAN change). Adults (from being a teenager to ultimately becoming a senior) can go through four stages.

As teenagers, we generally start out with the instrumental lens, where we focus on trying to follow the rules and strive for the rewards associated with this. In this stage, we are following the rules for the sake of the rule, not because we try to fit in or because we see the benefit. For instance, as a child and teenager I just studied, not because everyone did or because I knew it would help me, but because this was my rule. And I got rewarded (with praise) by my parents if I did well, and faced their disapproval and disappointment when I didn’t.

Most teenagers, however, do not stay with this lens for too long, and sooner or later adopt the socialized lens. Here, we try to align with social norms and expectations. For instance, as a teenager we often do what everyone else does, what is expected in our peer group. The most extreme example are gangs, where the social pressure is so great that teenagers commit crimes.

We can maintain the socialized lens for our whole life or we can move on to a self-authoring lens, where we focus on our own internal values without considering what we are supposed to do. This then can lead on to a self-transforming lens, where we critically assess our own value system and are open to those of others. The self-transforming stage is usually only reached late in people’s lives, if ever.

Usually we are not aware of what lens we use to assess the world around us and to make decisions. Even if we are aware, this does not mean that we can just change our lens. Changing mental lenses is a gradual process that depends on exposure to social groups and role models and a lot of reflection.

Robert Kegan, clearly self-authorizing …

Why is knowing about these developmental lenses important? I must say that for me learning about this was really powerful, because it helps me to interpret behaviours of colleagues and students with whom I interact. I often wonder why others behave so differently from me and make decision that make no sense to me. But I realize now that people’s decisions and actions can often be explained by their different lenses. I realized that many adults, at least in their work life, tend to use a socialized lens and do what is expected from them, instead of thinking about what may be good for them.

When it comes to students, knowing about the lenses helps me not to judge, because the students could inhabit different lenses due to different backgrounds and external circumstances. More importantly, it helps me to realize that students are moving and may be on their way to develop a new lens, and that I can even try to help them to achieve this.

Not taking the lenses into account can also lead to misinterpretations. For instance, if a student wants to do an internship, it could be because it is a requirement for certain jobs (instrumental lens). It could also be because everyone else does it (socialized lens) or because the student consciously decides that doing an internship is the best to help him to her to achieve their goal (self-authoring lens).

Based on what I learned, it is also important to remember that people can have different lenses in different situations or areas of life. However, my own experience is that if someone has a self-authorizing lens, he or she tends to apply this to all areas of life.

Isn’t it an amazing concept that we can actually authorize ourselves to do something!

On work-life balance

One of the greatest insights from attending my personal coaching program last year was to learn about the assessments that create the so-called work-life balance.

Of all the Profs in my department, I used to be the only one who always leaves his door open. This has changed slightly recently, because my office neighbor has decided to also leave her door open. (This means that I now have to close mine when I meet students or attend online meetings.)

The reason why I leave my door open is not because I am trying to be different, but because literally every Prof that I have ever seen in the US or the UK left his or her door open. So it was the natural thing to do. The main reason why all these Profs leave their doors open is of course to be more accessible, to send the message that it is okay to disturb them and ask them things.

This raises the question of how I can get work done that requires concentration. I found an answer to this important question many years ago in an amazing column in the Journal of Cell Science by Prof. “Mole”, who shared that he gets his important work done BEFORE coming to his office. And this is the approach that I have also adopted for many years. Working outside where people can see me proved so much more productive.

Nonetheless, there is one major problem with leaving the door open. Other people can see what I do, whether I work or I don’t.

Now, one would think that the most important thing is not whether someone works constantly, but whether someone gets his work done and does it well. In spite of this, I have to admit that if other people see me not working (sleeping, checking out music or news), it bothers me. But why should it?

What I have learned is that this is primarily a problem of trying to maintain a certain image. In fact, in many things we do we are more concerned with our image than with the result. And one area where this is very obvious is the so-called work-life balance.

In most work places, there are two types of workers. One type always works long hours and overtime, is always available for last minute meetings and always willing to take up last minute assignments.

On the other hand there is the employee or leader (or researcher) who always leaves on time because he or she values his family greatly. To make up for spending less time at work, he works very efficiently. If there are urgent uncompleted assignments, she sometimes completes them at home in the evening if necessary.

Both types of employees could be equally productive. Nonetheless, the former is likely to be considered more dedicated because he is always there and always available, as this is the image she conveys. And work places that are badly organized and non-functional usually value this kind of image (and people who help to compensate the lack of organization and functionality by being always available are considered dedicated or committed). Hence, a poor work-life balance is often due to the workplace culture, due to the work environment valuing so-called “commitment” to make up for poor workplace organization.

For most people it is perfectly possible to be productive at work AND have a meaningful private life. It is not a question of EITHER/OR. All we have to do is to adjust our work commitments so that there is enough time for the family and personal pursuits. However, what is not possible is to spend enough meaningful time with our family or on our hobbies and at the same time maintaining an image as a 100% dedicated worker who is always present and available.

Hence, it would be wise to not be so concerned with our image and to choose a well-organized and functioning work culture (or create one), which focusses on preventing unexpected emergencies and last minute tasks and values results over time spent at work.

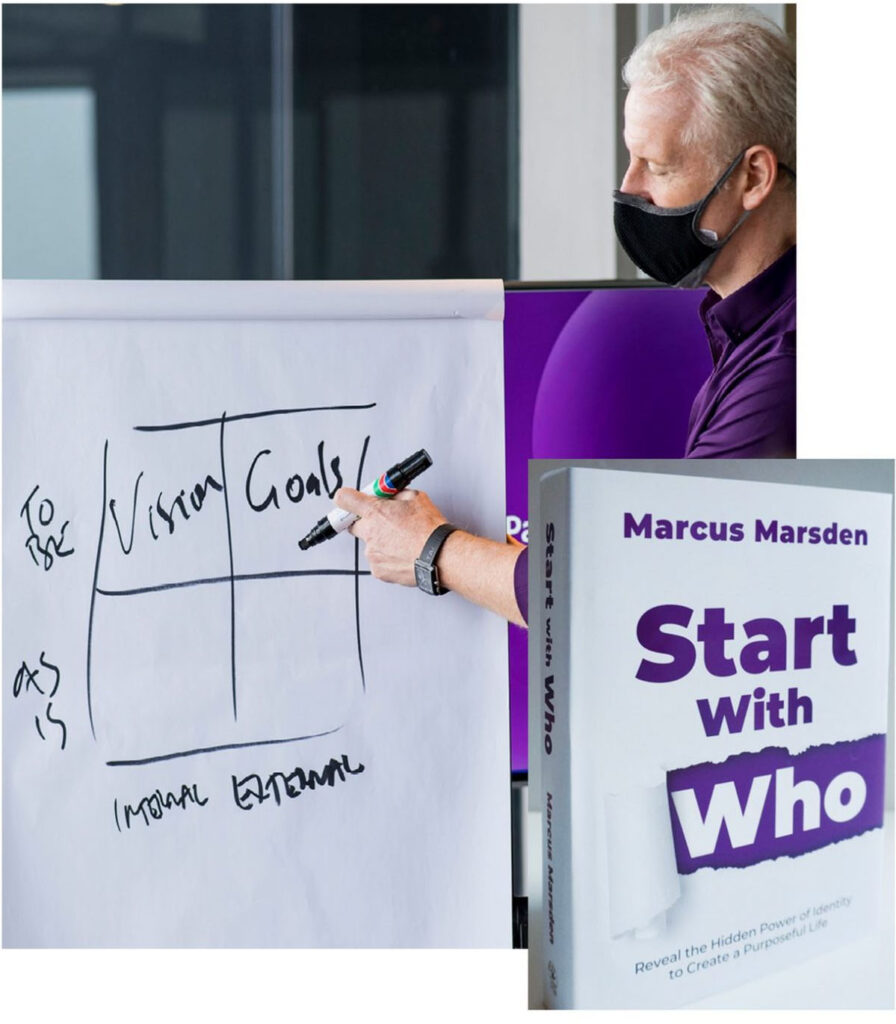

A great book on coaching: Start with Who!

Much of the insights on the work-life balance discussed above I owe to the teachings of Marcus Marden, Managing Partner of The Coach Partnership (a Singapore company that trains ontological coaches) and chief instructor during our coaching programme. I just finished Marcus’ excellent book “Start with Who”. which helped me to get a lot of new insights about myself.

Start with Who! – A very insightful and impactful book about achieving goals by Marcus Marsden

A big advantage of the proposed approach to start with WHO is that we can become a different (for instance a health-conscious) person immediately, without first having to prove this to ourselves and to others by building up a track record and undergoing a physical transformation.

Starting with the “Who” encompasses to embrace a new mindset and make this mindset part of our identity. For instance, I can adopt the mindset that I am a person who eats healthily and who exercises regularly.

Changing our mindset often requires to realize and change some of our assumptions. For instance, saying to myself that I NEED to have sugar in my tea may sound like a fact. But it is only my personal opinion. There are plenty of other people who prove that drinking tea without sugar is possible. As much as I can maintain that I need to drink tea with sugar, I can also make the opposite statement: “I don’t need sugar in my tea.” Having made this statement (to myself and others), I can then move on to make drinking tea without sugar part of who I am (my identity).

Making these decisions has a number of consequences. Firstly, it eliminates to a large extent the need for willpower. For instance, if I already decided that I eat healthily, I would not even consider certain types of food. If someone offers me chocolate, I can immediately reply “Thank you, I don’t eat chocolate.” This is very different from having to consider a choice every time an offer is made.

This is also one important reason why being a Vegetarian is a good way to eat more healthily and lose weight. Most unhealthy meals contain meat. By declaring that I don’t eat meat, I immediately eliminate the need for willpower to stay away from these choices.

Author Marcus Marsden also points out one other advantage of starting with the “Who”: We have the unconscious drive to prove ourselves right. If I say to myself that exercise at my age is too difficult, I will perceive the experience of exercise being strenuous or tiring as a confirmation of my belief. On the other hand, if I am someone for whom exercise is part of my identity, I will view difficult exercise as evidence that I am really exercising, which confirms my belief about my identity.

Making exercise part of Who I am also elevates the importance of my goal. If exercising is part of my identity, I will make sure that I dedicate the necessary time, because I have defined exercise as something very important for me.

In other words, it is ‘Who we are’ that determines the outcome of a goal. For instance in the case of exercise, am I exercising because I feel I should but prioritize work and personal enjoyment over my health? Or am I someone who makes his fitness and health a priority?

The approach of starting with the Who has proved very successful for my exercise goals. Exercising has become part of my identity and I no longer have to force myself to go out and exercise. It is something that I do almost every day because the alternative to NOT exercise regularly does not exist for me.

The Importance of Saying No

Many years ago we used to have a big and fun lab. We used to go bicycling at East Coast Park, meet up for card games, go bowling and even run together on the NUS track every Wednesday – until somebody in my lab finally hinted to me that many of my students did not actually enjoy various of these activities. This made me very disappointed.

The example highlights two important points. Firstly, communication is really important. Secondly, we must be able to actually say No sometimes. Not saying No is a problem because it creates unhappiness for both the person who makes a request (me organizing things that people don’t actually want to do) and the person who receives the request (the people who are supposed to participate).

Everybody would probably agree that when we are asked to do a task or join an activity, it is important to say No when we are too busy or unable to help or join for any other reason. This helps us to stay happy and be able to spend time on the things that are important to us, and it also sends an important feedback message to the requester so that he can adjust his requests in the future.

Yet, many people, including myself sometimes, find it difficult to “Just say No”. There may be various reasons for this. These include for instance not knowing if the request is part of your job description and hence difficult to reject, not wanting to disappoint the requester, feeling obliged because the requester has helped us in the past, not wanting to give the impression that one isn’t interested in joining team activities, etc.

One common reason for not saying No is that people often wrongly think that carrying out a request is a duty. For instance, when I ask people in my lab to do things, I usually have to say “It is okay to say No!” for my lab members to even consider this option. This shows that it is really important to know what type of requests fall into our area of duty or responsibility, and which requests we could potentially turn down. And if we are this not sure about it, then we should ask. “Is this a request that I can say No to?”

If we DO reject a request, it is important to do it tactfully. We could acknowledge that the request is very important to the requester and thank him or her for the invitation or thinking about us. We could then explain why we are unable to carry out the request, but that we would be happy to consider other requests in the future. Of course, sometimes it is also important to show “good will” and for instance join team activities to get to know work colleagues better. Through saying Yes, we also build up our emotional bank account with the requester, which makes it easier for us to direct our own requests towards them in the future.

When I receive requests, my general thought process is to first consider whether I have the capacity to carry out the request and whether it is part of my job description. If I do not feel obliged, I consider whether I could genuinely make some difference to the requester or her cause or whether it is an opportunity for me to improve in a meaningful way. If either of the two factors applies, I would say Yes. If neither applies, I would say No.

It is very important to consider whether we could make any kind of impact when agreeing to a request. This is not only because it feels nice to know that our actions make a difference. It is also important because carrying out a request is an opportunity to advertise ourselves. If we put in a lot of effort to make the result good, other people will notice. If we spend minimum effort, other people will also notice. Hence, if we are not able to put in enough effort, it would be better to turn down the request.

When considering whether to carry out a request it is NOT important how big the impact we make is. For instance, if we agree to give a talk for a small audience, it is still an opportunity to gain experience and advertise ourselves. We will not be asked to present to a large audience unless we first build up experience and credentials.

In conclusion, when receiving requests we should consider whether accepting the request is a good opportunity to build up our reputation and a chance to learn something new. By immediately saying No we may miss out on new opportunities.

Another important point to realize that there are more possible answers than just Yes or No.

For instance, a possible response is to ask for time to consider the request. In this case, we should express clearly when we will convey our decision to the requester. Even if in the end we reject the request, this approach has several advantages compared to a straight rejection. Firstly, we have the time to seriously consider the request. Secondly, we signal to the requester that we are taking the request seriously. And finally, the requester is likely to prepare for the possibility of a rejection of his or her request and may come up with a contingency plan.

What about requests that fall into our responsibility, but that we are too busy to carry out well without compromising other tasks or our personal priorities. Again, here it is important to realize that our answer does not have to be a straight Yes or No.

For instance, we can negotiate. We can ask for a later deadline. Or we can agree to do part of the work.

We should also try to get at the core of the request, by finding out what the requester really wants or needs. For instance, if I were to ask someone in my lab to clear out the cold room, but that person feels unable to carry out this request due to his other commitments, he could respond by asking why I am making this request. For instance, do we need space for some new equipment or is there a safety inspection coming up. The former could be done easily without clearing the whole cold room, whereas the latter could be achieved with less individual disruption by distributing the task among different lab members.

When I think back of the times when I askied my lab members to go for a run every week, I wish they would have reacted differently. For instance, they could have ask about my motivation behind this suggestion – is it to spend time together as a lab or to help everyone to keep fit. And depending on my answer, they could make alternative suggestions.

Sometimes it is quite apparent that our request or question serves a different purpose from what we are literally asking. For instance, if someone during an activity says “Are you not hungry?”, he or she probably feels hungry herself and wants to take a break. To avoid frustration and conflicts it is better to express our request explicitly. If we are on the receiving end, it is again important to understand and respond to what is behind a question or request.

What these examples show is that whenever we make a request, we try to take care of something – a problem, a concern, an opportunity, a feeling. It is important to understand (and not guess) what the speaker is trying to take care of with her requests and this is what great communication is all about. Likewise, if we express a request, it is important to reveal what is the reason why we are making it, or what we are trying to care of.

Another common mistake when trying to make requests is to only state an observation. For instance, declaring to my lab members “We need to clear out the cold room” is not a request and I should not be surprised if this statement does not incur any actions.

In my Newfield coaching program, I have also learned that there are a number of questions we should ask ourselves before making the request.

1. Am I owning the request? In other words, do I show that I care about what I am asking about, or do I just channel a request from the top down to team members without showing any attachment to what I am asking for.

2. Is the listener present and able to receive my request, or is he or she preoccupied with other things on her mind?

3. Is the person receiving the request able to carry it out, or do I need to provide any assistance?

4. In the context of the request, is what is obvious to me also obvious to the listener? Or do I need to provide additional information or context?

5. What exactly does the person who receives my request need to do to make me satisfied? Or in other words, did I clearly state my conditions of satisfaction?

6. And finally, what is the deadline or timeframe of my request?

Most iimportantly, it is a good idea to check if the listener has understood the request in the way that it was intended. If the listener agrees to carry out the request, we need to check on the progress and provide feedback (which could be as simple as saying “thank you”). The worst scenario is if we carry out a request but nobody ever asks or comments about it.

What about the situation where we do make a clear request and get a No reply. I usually interpret this as a rejection. Why? Because I measure my success by whether the other person is going to say Yes. If he or she says No, I have failed.

This is not a good mindset, as I have recently learned from the Coaches Training blog from Master Coach University. The problem with this mindset is that it sets me up for unhappiness. What is more, the blog highlights that the approach of aiming for a Yes answer makes it more likely for the other person to say No. The person who receives our request feels like she is doing it for us and may start to question my real motive. In addition, my own fear of rejection is likely to trigger tension and resistance in the other person.

Hence, a better mindset is to not display an attachment to the outcome of a request. Without the fear of rejection it is also much easier to make a request in the first place.

According to the blog, when we invite someone to do anything, our motive should be to help the other person find or do what is best for them. With this approach any decision that the other person makes is a success, as long as the decision is honest. The request becomes an offer that helps the other person to do what is best for them. If they say yes, we know that they do so because they really want to. After all, who wants to work with someone who would rather not work with us.