Supervising undergraduates in the lab – Is it a good use of our time?

One of the most fun and gratifying aspects of being a University lecturer is to supervise undergraduate students in their research projects. As lecturers, we have the privilege to often be the first to introduce students to research. We get to see their excitement when things work out. We get to witness their amazing improvements, where within a few months they go from having absolutely no clue to running experiments on their own.

Interacting with undergraduate students has always given me great joy and hence I have often wondered why any Professor would delegate this task to graduate students, postdocs or research assistants. Yet, many principal investigators do. I even heard one professor say once that he does not actually know the names of the undergraduates in his lab.

It is tempting to give priority to writing grants, attending meetings and networking. All of these are important. But it is equally important to remember that as educators, we can have a huge impact on students performing research projects in our lab.

When I was an undergraduate student, learning through my research project had the most lasting effect. In fact, I still remember most things that I learned through my research project, compared to almost nothing of what I learned in my coursework. The main reason for that is that my motivation was very different. When I was in the lab, I needed to learn things, because what I learned was necessary to plan my experiments and understand and interpret my experimental results. It was also interesting to read about my research area because it was so relevant to what I was doing. In contrast, in my formal classes I often could not see why what we learned was important.

In addition, I learned many practical and transferrable skills through my research. I even managed to publish a couple of papers. And I realized that I really liked scientific research. For all these reasons, I have always felt that there should be much more emphasis on teaching through research projects, ideally from year 1 onwards.

Unfortunately, not all undergraduate research projects are perceived as satisfactory by students and there is a considerable percentage of students who leave their research projects early, or consider doing so. There are a variety of reasons for this, including too difficult or boring projects, a poor lab culture and personal conflicts between the undergraduate student and other members of the lab.

A very interesting study that I read recently looked at the effect of undergraduate student supervision as a factor for whether the students complete or discontinue (or consider discontinuing) their research projects. According to the paper, prior studies related to this topic have been primarily done in research-intense universities, like NUS. The authors point out that the way undergraduates are being supervised is likely different between research universities (that award undergraduate and PhD degrees) and smaller institutions that do not have PhD programs and award only Master’s and undergraduate degrees. Knowing about these differences could perhaps help to understand the reasons why undergrads are dissatisfied with their research experience.

One major difference is that Master’s or primarily undergraduate degree universities and colleges do not have PhD students and postdocs who could act as mentors for undergrads. As a result, in those institutions the professors are more likely directly involved in the supervision of the students. Hence, the authors of the study asked whether the persistence of undergraduates in research programmes differs between institution types and if yes, what factors may be involved in this.

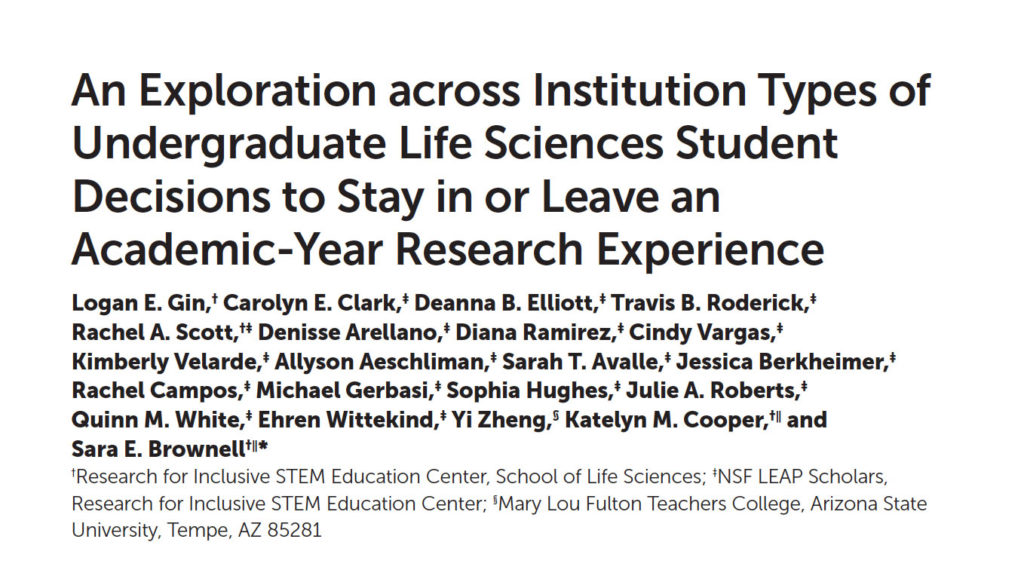

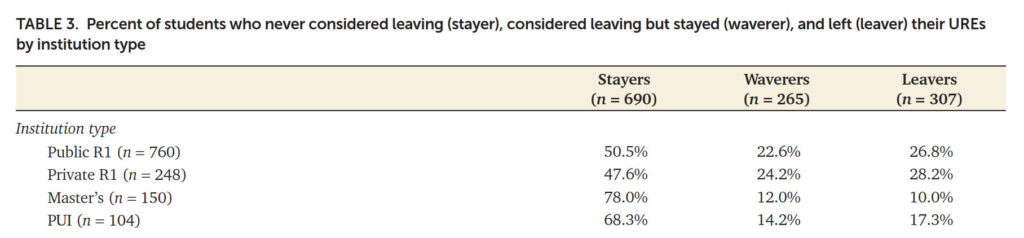

The study found that students in Master’s granting and primarily undergraduate universities and colleges were less likely to leave their research project or consider leaving it than students at research intense universities. For instance, compared with students in public research-intense universities, undergraduate students at Master’s granting institutions were 4.5 times less likely to leave their research project. Similarly, students at primary undergraduate institution were 2.8 times less likely to abandon their research labs.

Undergraduate students in Master’s degree granting or primarily undergraduate institutions (PUI) are less likely to leave their research projects compared to undergraduate students in public and private research universities (R1)

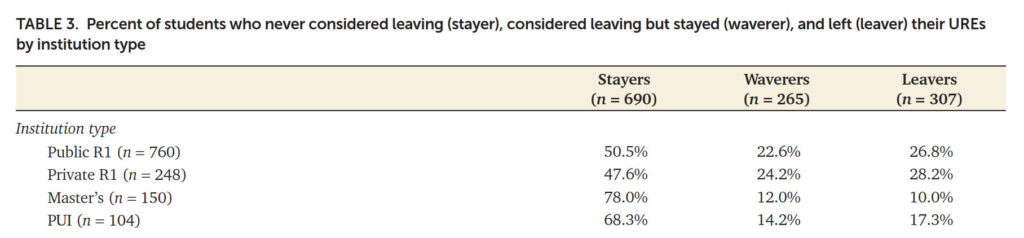

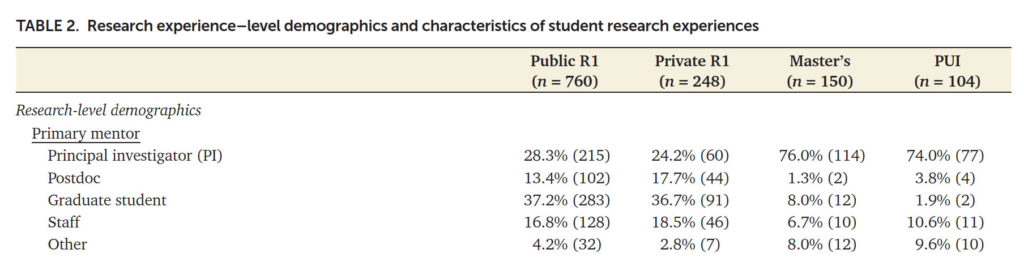

When comparing the characteristics of the research projects in the different institutions, the most striking difference was who was mentoring the students. In Master’s degree granting and primarily undergraduate institutions, the Principal Investigator of a lab guided undergraduate students directly in 76% and 74% of cases, respectively. In contrast, in public and private research-intense, PhD granting universities, very few Principal Investigators (28% and 26%, respectively) mentored undergraduates directly. Instead, in the majority of cases the undergraduates were mentored by graduate students.

Undergraduate students in Master’s degree granting or primarily undergraduate institutions (PUI) are more likely to be directly mentored by the Principal Investigator/professor

The researchers found no significant differences between the different types of institutions in the number of hours students spent on their research, in the percentage of students who were paid and whether modular credit was obtained for the research projects. Hence, whether or not undergraduate students wanted to stay in their research programs correlated best with who guided them. This is of course only a correlative effect, and it would have been interesting to study if students who actually left their research program (or were considering it) were less likely to be mentored by the Principal Investigator of a lab.

Why would being directly mentored by the Professor make a difference to the experience of undergraduates in research projects?

The article discusses a number of possible reasons. One reason is that students who are directly supervised by the principal investigator are more likely to be doing their own projects, as opposed to helping with the project of a more senior lab member (like a graduate student). By doing their own project, undergraduates are given more ownership and autonomy in their research, and they can use more creativity. Based on my experience, ownership, autonomy and creativity are very important for students to be motivated in research.

When I was an undergraduate, I was always directly supervised by my professor, and I had my own project, which I discussed with my Prof regularly. And because that is how I came to like and be excited about research, I have always used the same approach, irrespective of whether the students had some experience or were complete novices from high school.

The article also discusses that who is mentoring the undergraduate student also determines the quality of the assigned tasks. If there are no PhD students or postdocs involved in the project, the undergraduate student gets to do the more interesting and complex parts of the project himself or herself. In contrast, PhD student or postdoc mentors may assign tasks to undergrads that they themselves do not want to do, like preparing reagents, repeating experiments or doing control experiments.

From the perspective of the Principal Investigator, I have been spending time with each student not only because that is how I used to experience research as an undergraduate, but also because it is one of the things I enjoy about being a Prof. In addition, being directly involved in the undergraduate student supervision also has a number of other advantages. It helps me to know what is going on in the lab and to stay connected with practical lab research, and it forces me to keep up to date with methodological aspects. This in turn enables me to continue to be able to guide students and troubleshoot problems. And after all, being involved in lab research is usually the reason why we started this career in the first place.

With the right supervision, undergraduates can also be very productive and even publish papers. And most importantly, seeing undergrads develop and be excited about what they do sparks great joy in me!

On the other hand, being directly supervised by the professor could also pose some difficulties for undergraduate students. For example, the undergrads may feel less comfortable to share concerns regarding their work or problems they face with a professor as compared to a graduate student or postdoc mentor. I feel, however, that this depends on the supervisor’s approach. All if often takes is considering the possibility that the undergraduate may face problems and asking about it.

On the side of the supervisor, spending time with undergrads takes time and could limit our success in terms of securing grant money and publishing high impact papers, and this is one major reason why many Principal Investigators delegate tasks related to undergraduate supervision. Ultimately, everyone has to decide what is his or her priority and how one defines success and impact. Some professors also manage to find a middle way by showing care and interest in the undergraduate students and their projects without guiding them through every step of their journey.

Me as an undergraduate researcher with my Prof June, who was also my direct research mentor

Me as an undergraduate researcher with my Prof June, who was also my direct research mentor