WEEKLY HIGHLIGHTS 2025 FIRST HALF

Free Will

I recently attended a very interesting philosophy lecture by Professor Larry S. Temkin, entitled “Pluralism and egalitarianism”. In his lecture, Larry Temkin discussed human health and access to health care from an equality and comparative fairness perspective.

Prof. Temkin elaborated on various interesting questions, such as the conflict between equality of opportunity and the necessity of rationing in the context of scarce medical resources, and the importance of the “first come, first served” principle. He discussed the fictional scenario where a patient with a low likelihood of survival is placed on a machine to potentially save the patient’s life. Subsequently, another patient arrives at the hospital who has a much higher chance of survival, but also needs the machine that is used for the patient with a low survival chance. This is an obvious ethical dilemma, and also not a far-fetched scenario, especially during conflicts where availability of doctors and nurses, medications and medical equipment is limited.

However, the most interesting topic to me was the issue of individual responsibility to one’s own health and the question of whether acting irresponsibly with regards to one’s health should affect access to or cost of health care. In other words, should someone who “chooses” unhealthy habits receive the same care and pay the same as someone who consciously tries to make healthy choices in his or her life.

This then raises another important question – are humans actually free to choose how healthy they live, or is their behaviour towards health, or anything else for that matter, determined by their genes, social upbringing, environment, socioeconomic status etc. In other words, does free will to choose one’s behaviour truly exist?

A book recommended by one of my students, which I started to read, argues that from a scientific perspective free will does not exist.

In his book “Determined, A Science of Life Without Free Will”, author and neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky argues that we have much less free will than is generally assumed and that we are highly constrained in terms of our behaviour. To substantiate this claim, he cites and explains much recent scientific evidence.

Robert Sapolsky believes that if we were to believe that we have very little free will, our lives would improve. It could for instance lead to forgiveness and better understanding between humans and for seeing “the absurdity of hating any person for anything they’ve done”.

Of note, the question of whether free will exists has never been proven or disproven and is subject to an ongoing debate between so-called determinists and compatibilists.

Determinists such as Robert Sapolsky are of the opinion that the decisions that we make are determined by the neurons in our brains. Our neurons become activated or deactivated as a result of the sum of their inputs, which in turn are ultimately determined by genetic (and epigenetic) as well as environmental factors and are not subject to free will. As such, something that occurs happens because of what became before that, and so on. In order to understand a behaviour, one needs to understand what happened seconds before the behaviour as well as minutes, days, years and even millennia before the behaviour occurred. Needless to say, the factors, or inputs, that determine our action at one time are nearly infinite, ranging from our levels of various hormones to the specific microbes in our gut (microbiota) and the metabolites they produce.

On the other hand, there are the compatibilists, who include most present day philosophers. Compatibilists believe that our actions are in fact determined, but that we nonetheless have free will.

I personally agree with a compatibilist view. On the one hand, I often find it very difficult, if not impossible, to control my will in the moment. For instance, if I have planned to go for some difficult exercise but when the time comes do not feel motivated, then there is little I can do to change my mind. It feels nearly impossible to ‘force’ myself to do something that I do not want to do.

Similarly, given the choice of a free delicious meal, most people would indulge even when they know that it would be better if they didn’t.

However, I believe strongly that we can influence our free will, not in the moment, but by building habits or structures that prevent us from having to make decisions at moments when we may be emotionally weak.

In a very insightful commentary by Dr. Alexander Horwitz on D. David Puder’s Psychiatry podcast website, I came across a couple of very fitting quotes by two contemporary philosophers:

“Daniel Dennett in response to the idea that we have no control over our biology or environment noted that autonomy is a process that initially is beyond one’s control but as time goes on, we have the opportunity to refine our activities, choices, thoughts, and attitudes. Similarly, philosopher Robert Kane has noted that free will is more than free action and concerns what he terms “self-reflection.“

And finally, “… psychiatrist Sean Spencer … believes that we have the ability to exert free will during optimal moments and not while in crisis“.

As such, while in “crisis moments” we often are incapable of doing what is best for us (or avoiding what is bad for us), we can use our willpower to create “optimal moments” during which we reflect and come up with approaches to avoid these “crisis moments”.

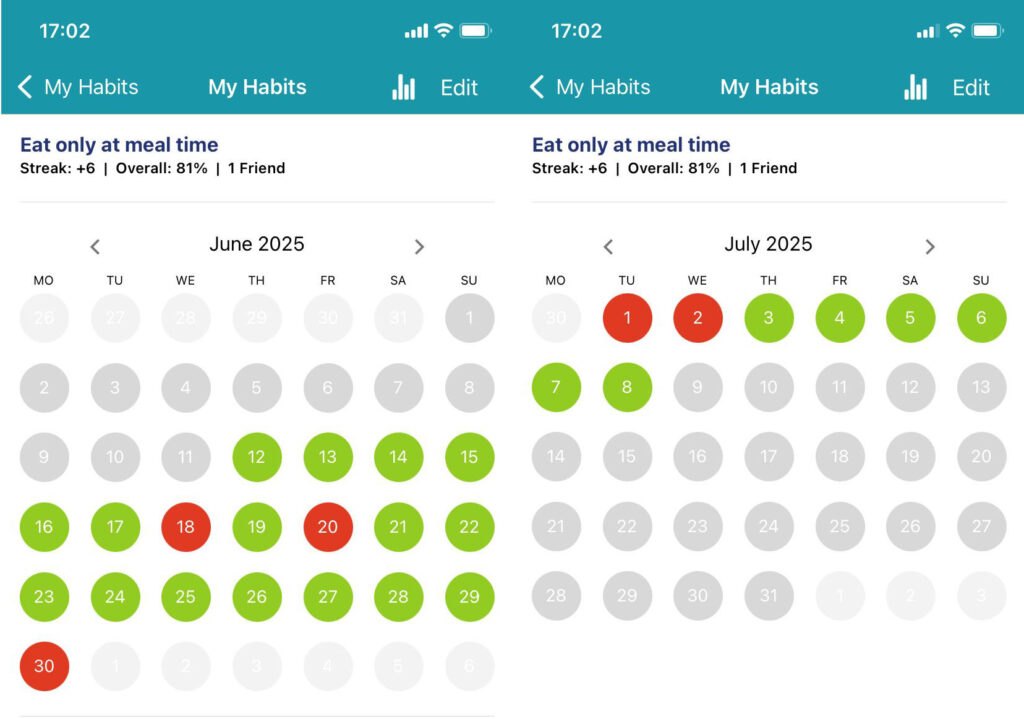

And this is precisely what I have done recently to stop myself from constantly feeling tempted to snack between meals. I committed (using my Habitshare app, which I share with my accountability partner) to only eat during my planned meal times (with the exception of being allowed to eat apples inbetween). So far, this approach has worked out well!

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 30 JUNE – 6 JULY

Spending time with my family

I spent a wonderful week at home with my parents, during which we did many memorable things. We went on a long bicycle tour (which became even longer because we got lost several times when we were trying to head home). We also made a trip with my extended family, including my sister, nephew and niece, to the baltic sea, where I managed to submerge myself for about 30 seconds in the ice-cold sea water. It was also fun to relax at my parents home, at the local mall food court or at a nearby lake, where I went for a (slightly longer) swim.

I already look forward to my next holiday at Christmas!

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 23 – 29 JUNE

What exactly determines whether professors are successful?

I recently read an interesting article in Science magazine. The article was penned by a new Assistant Professor who described the struggles and difficulties he had to overcome in order to finally secure his tenure track position.

The author Jary Delgado faced various challenges, including a non-privileged background and origin from Puerto Rico, scarce research funding during his PhD, extremely difficult job-hunting during the 2008 economic crises, a conflict-ridden relationship with a supervisor and setbacks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jary Delgado describes how unexpectedly his track record of being perseverant played a role in being awarded a faculty position. He writes:

“The interviewers were friendly and I felt good about my performance, but I wasn’t expecting the offer I received a month later. To my surprise, I later learned the committee had valued a factor rarely considered in an academic world obsessed with publications and impact factors: my resilience.“

As the quote suggests, perseverance seems to be a rather uncommon criterion for hiring academic faculty. I would argue that most researchers who succeed to become Assistant Professors have encountered relatively favourable conditions during their training. Indeed, without experiencing favourable conditions during one’s PhD and postdoc it is very difficult to achieve the outstanding publication record that is required to be considered for Assistant Professor positions in many institutions.

Jary Delgado argues that scientists who struggled to overcome professional and personal hardships may in fact have an advantage when coping with the challenges that young faculty will inevitably face. In other words, these researchers have developed the “resilience to get through tough times”.

I do agree about the importance of resilience wholeheartedly. Nonetheless, I must admit that among faculty that I know there is no good correlation between how difficult someone’s path to landing a faculty position has been and how successful he or she has been as a researcher. In fact, if anything I feel that there is a trend that those who experience fast success as a trainee tend to continue to do so when they are a professor, suggesting that success is more dependent on how researchers work.

What is true is that researchers who have worked hard as a student and postdoc tend to work hard as a professor. But hard work does not necessarily translate into research success.

This then raises the interesting question on what exactly determines success, in particular research success, of academics.

This question seems particularly relevant for universities and colleges, who invest greatly in recruiting new faculty and whose success as an institution is linked to the success of their researchers.

Based on my own experience of the hiring process, the primary focus is on past success (mainly in the form of high impact research papers) and alignment with the university’s strategic research directions. However, a search of this topic suggests that there is little evidence that those factors are particularly good predictors of future success.

The question of what determines faculty’s research success is also of interest to me personally because despite considering myself very knowledgeable and being able to come up with interesting questions, I have not been very successful as a faculty in terms of my research achievements.

Of course, as I have discussed previously, “success” is a highly subjective term, and in terms of making an impact on students, which could be considered as the primary role of a university professor, I think of myself as being successful. However, most research intense universities consider (probably wrongly) that making an impact on students is the default outcome of hiring any professor, and thus primarily value research papers and research grants.

So what factors actually do predict research success of university faculty?

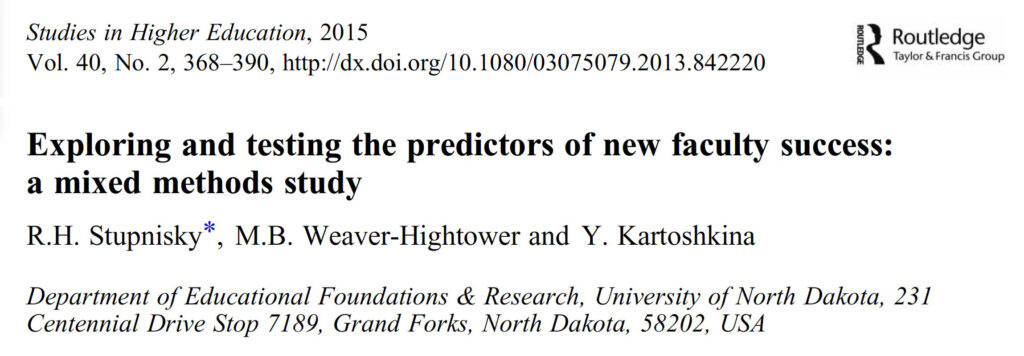

According to a paper by Stupnisky and co-authors, published in 2015 and entitled “Exploring and testing the predictors of new faculty success: a mixed methods study”, there are three recurrent themes that consistently emerge in the literature. These themes are “clarity of expectations, finding balance, and collegiality”.

Upon reading this article I feel that these three themes resonate with me well. As such, I would like to discuss them in some detail.

Clarity of expectations

Stupnisky et al. highlight that many new professors lament a lack of clearly expressed expectations, or frequent changes in expectations, as reflected in the statement ‘tenure is like a moving target.

In truth, I personally feel that it seems rather obvious that what matters most is doing impactful, original research, for which one’s research papers and record of obtaining external research funding function as an important proxy. The main problem appears to be that many young Assistant Professors, probably including myself in the past, are not taking the right steps to meet these expectations. What could be helpful, and what was certainly lacking in my own case, are guidance and discussions about what the right steps, best approaches and most promising directions could be.

Finding balance

With regards to the second factor, finding balance, Stupnisky and co-authors highlight that there are two types of balance – balance between the professional roles of research, teaching and administration and balance between professional and personal life. I believe that both of these types of balance are important, and as a new faculty I have neglected both.

Important qualities to achieve balance include for instance good time management by establishing routines, developing ‘priorities, being able to delegate tasks and learning to say no. I certainly lacked these qualities when I started out as an Assistant Professor, and it took me many years to develop them.

Collegiality

The final factor is collegiality, and I could not agree more about its importance. Success as a young Principal Investigator requires not only the exchange of ideas with others, but also mentorship. As a young faculty, there is the temptation to focus primarily on our own work, but investing time to build relationships with senior and often influential faculty is certainly beneficial in various ways. Even more important is to engage in scientific collaborations. Indeed, my own most impactful publication have come from collaborations. Yet, there have been too few collaborations that I have initiated.

Focus on meeting expectations, finding balance and valuing collegiality and collaboration are criteria that are relatively easy to spot when hiring faculty. They are also not that difficult to pursue as young faculty, provided we are aware of these requirements and take actions on them.

Although I cannot turn back the clock, I am very happy that things have worked out in the way they did and that I have found a way to make an impact that feels very meaningful to me.

Nonetheless, it has been useful to compare my own experience with that of young faculty featured in a series of articles called “Career pathways”, which has been published by the journal Nature Metabolism and which I will write about in one of my next posts.

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 16 – 22 JUNE

My teaching feedback – Part 2

In last week’s post I discussed the various positive aspect related to my teaching feedback for the past semester. However, the feedback comments also revealed that there was a handful of students who felt demoralised throughout the course. This is of course greatly concerning and prompted me to think about what makes the course discouraging for some students and what I can do to address these points.

In my post from two weeks ago I began discussing a very insightful book by Sheila Tobias (“They’re not dumb, they’re different”), in which the author describes the experience of non-science majors taking foundational physics or chemistry courses.

One particularly insightful case described in the book is that of Vicki, a senior in anthropology at the University of Nebraska, who audited an introductory physics course. Among all the social science majors in the study who took science course, Vicki felt the most discouraged. As such, her experiences may exhibit resemblances with those students who felt discouraged in my course.

Vicki stated that her frustration firstly originated from receiving poor grades on homework and short exams. Sheila Tobias writes: “Like the typical college student, Vicki had got into the habit of judging herself by her grade-point average, and when she found it difficult (as it turned out, impossible) to win honour grades in physics, she was frustrated and resentful.”

Secondly, Vicki had particular difficulties with timed tests. She stated:

“Why can’t I have the time I need to show what I know?” And also … “That [what I know] is not what they’re measuring. They’re trying to find out how I do in relation to others …”

A final contributing factor to her frustration was feeling stressed about the pressure to catch up due to her lack in background knowledge, particularly in math.

Vicki wrote in her reflections: “More than in social sciences class, I felt the pressure of not falling behind. Once I started to slack off, I would always slow too far down.”

She found herself having to spend too much time to pick up the missing mathematics background, so that staying on top of the physics course content became difficult.

As such, Vicki’s experiences identified three factors that likely contribute to students feeling discouraged in science courses:

1. Not doing well on interim tests.

2. Time pressure in tests and exams.

3. A lack of background knowledge, which makes it difficult to catch up with new course content.

All of these three factors likely also play a role in the frustrating experience of some students in my course.

What could I do to address these issues?

With regards to the first point, I feel reluctant to make the course problems, quizzes and tests easier, partly because solving challenging problems is one of the main factors that make my course interesting. What is more, the truth is that interpreting research data and answering real world research problems is difficult.

One major reason why some students have difficulties with solving these research data related problems, despite trying hard, is that they may have different backgrounds and as such lack relevant knowledge and skills. As Vicki noted:

… the “range of expertise” varied more in her physics course than in social science. She never got over the shock of having students leave a review session in the middle, or just when problem solving was about to begin. It was as if she were in a beginning language class with students, some of whom spoke that language at home. “In social science there are people who are more advanced than others as far as knowledge is concerned,” she wrote. “But in science the more advanced are more advantaged. They can better capitalize on their knowledge.”

As Sheila Tobias points out, the discouragement that the students who possess a lower initial level of mastery experience is even more pronounced because these students were in many cases used to performing well throughout their secondary school education.

To address this, one measure that I plan to introduce next year during the first half of the course is to divide up my weekly quizzes into an easier graded one and a difficult (aspirational) one, for which students only obtain marks for participation. Only during the second half of the course will I then make all graded quiz questions more difficult.

The way to improve is through practice. Hence, by providing the opportunity to practice solving difficult problems without applying a penalty for getting it wrong, the students may be more motivated to practice.

The second factor that contributes to student discouragement is time pressure in tests and exams.

Why do I make my tests so limited in time? Firstly, I always worry about setting exams that are too easy and that consequently do not test the students’ level of mastery well.

My reasoning is that if students are familiar with how to solve the problems in the exam, they will be able to do so within a reasonable time. In contrast, students who are less familiar will spend a large amount of time to look up their notes or read through the research paper that is the subject of the exam. The problem that students may spend large amounts of time trying to find an answer as opposed to coming up with their own answer is further exacerbated by the availability of chatbots (which thus far I have allowed in my exam due to the research data based format of my questions). As such, I try to avoid that large numbers of students finish their exams early.

That said, some students clearly do need longer to figure out problems than others. As such, it would be good to try to find a solution that provides more flexibility. A good compromise could be to allocate more time for the bulk of the questions but to also include a number of difficult questions with very low mark allocation. As a result, students who need more time are still able to answer the majority of the questions without losing too many marks, while faster students remain engaged until the end of the exam.

Finally, with regards to the lack of background knowledge, one student has suggested that I should “dumb down” the course. However, the course is in fact a year 2 course. Yet, many students choose to take the course during year 1, which means that these students choose to take a risk.

What is more, I feel strongly that a University course should be challenging in order to achieve its objective. While many other year 1 and year 2 university courses may convey more basic knowledge, I believe that university education is about meeting challenges and doing difficult things, provided that they are meaningful.

I do try to make students aware of the degree of difficulty of the course with my readiness quiz, which students can take before the start of the semester. Even though one student commented “… saying that people should drop the course and come back next time if they don’t really understand the prerequisite quiz doesn’t give students confidence in the teacher”, the point of the quiz is for students to determine if they are confident in themselves, or to take action to become more confident.

What I could do is to provide students at the beginning of the course with more awareness of the challenges ahead and with some advice on how to meet these challenges. This may include that it is necessary to study consistently, that students need to fill any gaps in background knowledge when they encounter them, as catching up with course content and concepts later on is difficult, and that success is proportional to the number of practice opportunities that students engage in. Another useful piece of advice is that it helps greatly to have a group of friends to work with all the time to explain concepts and solutions to problems to each other. It will be a good idea to include these tips in my course intro video!

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 9 – 15 JUNE

My semester teaching feedback

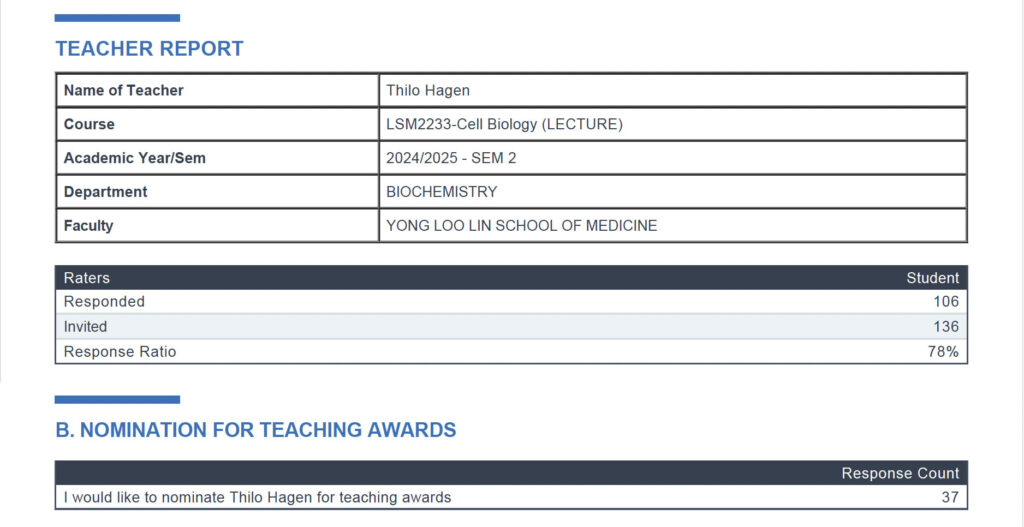

It is once again teaching feedback time. I received my scores and comments from the students who took last semester’s Cell Biology course, and overall the scores and comments made me very happy.

I was very pleased that my teacher feedback scores were my highest ever. They were even slightly better than back in 2020 during the Covid pandemic, when students tended to be more lenient with Professors and awarded more generous scores.

Most of all, I was happy about my “best teacher nominations”, both in terms of their number and the justifications that the students wrote. There were 37 students who nominated me for a teaching award, which is more than a third of all students who responded and more than one fourth of all students who took the course, and which is my best ratio of nominations ever.

I am very happy about this, not because it means that I might get a teaching award. (To be recognised with a teaching award one has to actually apply for it, which requires preparing a lot of documentation. And since the decision process is not very transparent, I have not applied for teaching awards in recent years.) The main reason is that getting this many nominations feels very encouraging. Even more importantly, the comments or justifications that many students wrote are simply amazing and have moved me greatly!

In contrast to my teacher scores, my course scores were overall only average. However, I am not too concerned about this, in part because of the way the questions are formulated.

For instance, the first question, “What is your overall opinion of the module?“, is so broad and undefined that as long as students have something about a course that they disliked, they would not give the highest score on the scale of 1 to 5.

Another question, “The integration of technology – blended learning, digital tools, AI, and online resources – has enhanced my learning experience.” must be very difficult for a student to answer, because it firstly implies that a course has in fact employed these tools. From a student’s viewpoint, it remains unclear if the expectation is that all of these tools should have been employed. How is a student supposed to rate a course that did not use these tools or used only some and if some of the tools were effective and others were not.

The third question in the feedback survey focusses on the difficulty of the course. As always, students rated my course as much more difficult compared to other courses, but as the verbal comments illustrated, a challenging nature of a course can be perceived as a negative or a positive experience.

Indeed, it is the verbal comments that are are always most insightful and useful. When looking at the negative comments, there were really only two groups of comments, both of which were expressed by many students (around 25 students each, which corresponds to one quarter of all students who completed the feedback).

Firstly, many students commented that the course content and in particular the application exercises and assessments were in fact too difficult. Again, this comment was not surprising.

However, on the other hand there was an equal number of students who in their positive comments expressed that they liked that the course focussed on thinking skills and not on memorisation. There were even some students who expressed that they enjoyed the challenging character of the problems.

As such, coming up with the right level of difficulty is always a balancing game. In Sheila Tobias’ book about students who felt reluctant to pursue Science majors, which I discussed in last week’s post, many of the students lamented that the exams were too easy. Too easy exams can lead to an overemphasis of luck and a focus on minor points, which can set back students who normally have good mastery of the course content. Although my problems are difficult, I feel that my tests reliably identify those students who have a good understanding and those who do not. Due to the curve grading, the difficulty level ultimately also does not negatively affect the student grades.

The second group of comments related to students essentially wanting more guidance. Although there are always students who want more “instruction”, I was surprised that nearly one quarter of the students requested more information in the lecture slides or to “lecture” more instead of letting students learn on their own through exercises such as my so-called self-learn quizzes.

In a self-learn quiz, the students learn by answering questions after discussing the problems with their neighbours and subsequently read the provided explanations. I in fact started using this approach in lecture 1, because one of my goals this past semester was to “lecture” as little as possible. This clearly came as a surprise to some students. One students commented “the very first lecture was quite the shock”.

What I personally think this illustrates is that students are used to receiving a lot of guidance and are not accustomed to a way of teaching in which they are the main driver of their learning. I firmly believe that the teaching approach is both engaging and effective. And compared to previous semesters where students often felt disengaged during the first lecture because they did not appreciate how the discussed concepts were relevant, I felt a much greater sense of satisfaction when seeing the students immediately active in solving problems, discussing with their class mates and learning.

On the positive feedback side, the most frequent comments related to the focus on application (more than 20 comments), on critical thinking as opposed to memorisation (also more than 20 comments) and on the fact that the students felt the course was “interesting” (around 15 comments). The latter I believe is primarily related to how engaged the students felt during classes.

However, what surprisingly received the most mentions were my passion for teaching and my dedication to students. Especially the latter made me genuinely happy!

Overall, the feedback confirms again that students care mainly about three things, whether the teaching focusses on applying knowledge, whether the students feel engaged and enjoy the course and whether the lecturer cares about the students.

I was somewhat surprised that only few students commented on specific aspects that are likely different from other courses, such as the team based learning and use of learning catalytics (positively mentioned by seven students) or the focus on research data. There were also only few comments on things that I introduced this semester, for example the various research talks that students watched throughout the semester (positively mentioned by two students) and the AI related discussions (positively discussed by three students and negatively by two). Presumably there is a limited number of points that students can focus on and write about, given that they have to provide feedback on numerous teachers and courses.

The course feedback also revealed that there was a handful of students who felt demoralised throughout the course. This of course is greatly concerning and I will be discussing this point separately in next week’s post.

There are of course always some comments that make me feel frustrated or defensive, such as those where instead of expressing their own experience or opinion, students speak on behalf of everyone else, such as “The module in general needs to be “dumbed down” for us students. The quizzes are way too difficult and the lecture content is impossible to follow at times.” If this was true, then all students should do badly all the time.

What feels even more discouraging are what I perceive as unfounded criticisms, such the feedback comment of a “lack of transparency of assessments or more of announcement of them?” In actual fact, the answers to all quizzes and tests, including the final exam, were published. Students also knew their scores and the class average for all assessments. With the exception of the final exam, they also knew their scores for every individual question.

Similarly, the comment that my “Canvas announcements that were given were often so lengthy that it was both tiring to constantly receive and at the same time difficult to discern important information” felt disappointing given that I make a great effort to make the course materials and announcements easy to navigate. Based on other students’ feedback, the way my materials are organised appears to be much more conducive compared to other courses. With regards to the announcements, I clearly indicated what the announcements were about and as such, students can choose whether they want to read it or not.

Another comment, “I felt like I had no way of improving myself and my knowledge to achieve the grades that I desired”, felt disheartening. With regards to the grades, students were given the opportunity to make up for a poor midterm test result if they improved in the final exam, in which case I counted their final exam result for both the midterm and the final exam itself. Indeed, more than one third of the students improved, some of them dramatically.

I was also surprised that two students criticised the (in my opinion rather limited) focus on generative AI. For example, one student commented “… I would like less emphasis on AI. I understand the importance of being aware and being able to differentiate between AI and human, but I think it is not ideal to spend one lecture on AI”. It seems to me that given how generative AI will affect the future, one almost cannot spend enough time on the subject.

Of course, there were many comments that made me very happy, including this comment that highlighted things that I in fact wanted to achieve in my course:

“I liked the content covered, Prof Thilo especially, as he puts in lots of extra effort to rekindle the scientist’s passion within me, and to get me to think creatively using my brain rather than constantly relying on ChatGPT/AI,, which will kind of makes me slave to the internet one day. This course, although tough to score, has taught me many life skills, such as perseverance and resilience, since everyone is trying to score A, and there are many people who will do better, I should not give up even if it is tough. I should just enjoy the learning process and do my best.”

I was also happy about the comment “Thinking is not limited to the syllabus and alternative hypotheses are encouraged.” These are things that I indeed wanted to achieve.

Finally, there were also a couple of very kind and moving comments:

“Not an improvement but rather to not be so stressed over the increasing usage of AI, he looks very stressed already :(“

“Prof I am saying this as someone who is simply concerned for your well–being please consider having more work–life balance.”

THANK YOU!

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 2 – 8 JUNE

Sheila Tobias: The second tier study

I have recently started to (re-)read Sheila Tobias’ book “They are not dumb, they’re different – Stalking the Second tier”. It is a rather old book, published in 1990. Yet, it provides some amazing insights into why students drop out of science courses or do not choose to pursue science in the first place. It also illustrates that not that much has changed in science education in the last few decades.

In her book, Sheila Tobias looks at college students who based on their academic abilities and high school prerequisites could have gone into science, but chose not to and instead pursued other fields of study that they considered a better option for themselves. The author refers to these students as “second tier”.

The book describes Sheila Tobias’ study aimed at trying to find out what happens when these second tier students took a university science course, with the ultimate goal to figure out what deters students from taking or continuing science.

The three commonly assumed reasons why students avoid science are that science courses are too difficult, that other fields are more interesting to students and that students perceive a lack of good job prospects. However, as the study reveals, the are other important reasons, including the classroom culture and the demands on students’ time. What makes this study so relevant is that these concerns have not changed in the last 25 years, and in some respects have gotten worse.

The first student, whom I focus on in this post, was Eric, an English literature major and summa cum laude graduate from Berkeley. He entered college with a strong background in mathematics and “the full complement of high school science courses”. Eric was asked to take an intense five-week introductory physics course.

The first thing that Eric noted on the first day of the course was that “no one seemed particularly excited … and everyone seemed either bored or scared”. Later, Eric observes: “In my literature classes … people took courses mainly because of interest in the topic or because they thought the professor would be good. It is not that a science course cannot be or isn’t interesting, only that it’s not required or expected by the students that it be so.” This seems sad, but it reflects a reality that I also encounter. Science students do not expect that a course might actually be interesting.

Eric was asked to observe his own experience of the course as well as that of his fellow students and ultimately to describe how the course was different from college courses in his own field of study. Learning about the things that Eric did not like about the physics course turned out to be very useful for me because it helped me to see what I am doing right and wrong in my own teaching.

The first thing that Eric found unsatisfactory was that there was only one answer to every problem and that there was no room for individual opinions and views.

Eric writes “that unlike [in] a humanities course, here the professor is the keeper of the information, the one who knows all the answers. This does little to propagate discussion or dissent. The professor does examples the “right way” and we are to mimic this as accurately as possible. Our opinions are not valued, especially since there is only one right answer, and at this level, usually only one [right] way to get it.”

My main goal in my own teaching is to teach students how to interpret and predict scientific data. I have to admit that the way my practice problems, quizzes and assessments are set up, there often is indeed only one “correct” answer. Although I do use student-centered and interactive approaches to make this learning process more engaging and fun, in this process there is no emphasis on individual opinions.

I believe that here lies one fundamental difference between literature and science studies. While in literature two opposing views can be equally valid, in science one interpretation is usually, based on available evidence, objectively more valid than other interpretations. In fact, one of my main goals is to teach students to make valid judgements based on provided evidence. Of course, scientists do frequently differ in their views on certain issues, but this is usually because they have obtained or have been exposed to different evidence or they view the validity of available evidence differently.

Eric suggests at one point to introduce dissent artificially, e.g. by exposing students to various potential solutions, and then let them discuss these options. This is in fact what most of the discussions in my classes are based on.

Discussing alternative solutions is important. Otherwise, as Eric writes, “students are only focussed on finding the right solutions [presumably because this is being tested) and not in real life ramifications of what they were learning”. In other words, in real life, students need to find the best among a number of possible solutions. As such, merely teaching students the right solutions is not sufficient.

This past semester I have also started to include some group exercises where opinions do matter and where there is not just one right answer. These exercises include a research-based creative thinking exercise to come up with a research hypothesis and plan and an evaluation of prose written by a human writer versus ChatGPT, as discussed two weeks ago.

Going forward, I want to include more individual opinion and reflection exercises, discussing questions like what it is that makes research interesting or discuss Artificial Intelligence related questions such as whether AI is likely to make our world and lives better and if and how AI progress can and should be controlled.

A second major critique in Eric’s evaluation was that in the physics course there was “no sense of community within the class”.

Eric writes: “When we got our exams back this week, everyone was concerned about how other people scored. I understand that natural curiosity and in my literature classes there was always some comparing done between friends. However, I’ve never experienced the intense questioning that has happened this week. Almost everyone I talk to at some point or another asks me about my grade. When I respond I scored an “A”, I get hostile and sometimes panicked looks. It is not until I explain that I’m only auditing and that my score certainly will not be figured into the curve, that these timid interrogators relax.”

Eric expressed that the sense of competition “automatically precludes any desire to work with or to help other people,” he wrote. “Suddenly your classmates are your enemies.”

He concludes: “If one is truly interested in reforming physics education in particular and science education more generally, de-emphasizing numeric scales of achievement and rethinking the grading curve is certainly one place to start.”

This raises once again the important question of whether grading students on a curve indeed precludes any meaningful collaboration.

Firstly, my position for the past years has been that in a society where grades are used to make all sorts of decisions, grading on a curve is necessary in large classes to maintain fairness. If on the other hand the society does not care about grades, then of course there would be no need for students to be overly concerned with their grades and hence maintaining a consistent standard would be less important. Perhaps, in the humanities grades are less important because what matters to succeed in finding jobs or in pursuing the career of choice depends more on other skills.

Secondly, is it possible to engage students in team work despite grading on a curve?

Based on my experience the answer is yes. My team based quizzes and activities have been very successful. Students value and enjoy these activities, despite the fact that they are ultimately graded on a curve. Factors that contribute to the successful implementation of group work include making the team work compulsory by grading it, but making the assessment low stake by awarding only low percentages or marks for participation. In addition, the team work must be based on real problems that provides opportunities for students to discuss, explain and persuade each other. As such, the lack of team work is not intrinsically linked to the fact that students are graded on a curve.

I would also add that when the class size becomes reasonably large, competition between students becomes a minor issue. For instance, the benefit of helping each other within a group becomes greater than the potential outcome that the fellow group members outperform a student. In addition, even if a strong student mostly explains things to a weaker student in their group, it is unlikely that the weaker student will become better than the stronger student. What is more, the stronger student will benefit by mastering the concepts better through the process of articulating them.

In conclusion, introducing group work is possible, even under conditions of curve grading. Introducing group work is also important. As such, I agree with Eric’s assertion: “My class is full of intellectual warriors who will some day hold jobs in technologically-based companies where they will be assigned to teams or groups in order to collectively work on projects. [But] these people will have had no training in working collectively.”

Eric highlights two additional points. Firstly, the physics course was simply not interesting and secondly, the workload was way too high and the pace way too fast.

What gets students interested in a science course?

Real interest can only come from engagement, and the best way for students to engage with science is by doing science, in other words, by trying to answer questions that have not been answered. Achieving this in a large classroom stetting is somewhat difficult. The next best tings we can offer students is to let them experience how scientists try to answer contemporary problems by engaging them with primary research data and literature and to mimic this process by letting them solve problems based on provided fictional or actual research data.

Eric writes: “The lack of community, together with the lack of interchange between the professor and the students combines to produce a totally passive classroom experience … The best classes I had were classes in which I was constantly engaged, constantly questioning and pushing the limits of the subject and myself. The way this course is organized accounts for the lack of student involvement… The students are given premasticated information simply to mimic and apply to problems. Let them, rather, be exposed to conceptual problems, try to find solutions to them on their own, and then help them to understand the mistakes they make along the way.”

Eric’s comments highlights that in addition to problem solving, the other important factor that determines how interested students are in a course is to create a classroom culture where students constantly engage with the lecturer and with each other.

With regards to the high workload and fast pace, Eric elaborates: “Most of the other students I have talked to take six or seven hours a day to do the work. .. Aside from the pure misery of devoting that much of your life to physics, I wonder how much they, or rather we, will retain. I think that a slower pace and more in-depth discussions of the contents would, in the end, prove [more] beneficial.”

I agree that in depth discussion of a topic is more useful to promote learning of concepts and being able to apply them to solve real world problems, as compared to covering lots of content on a level were students imitate what the lecturer teaches or demonstrates. Perhaps even more importantly, the high workload leaves students with little time to to pursue educational experiences outside their course work, which ultimately will be more important for their future.

A fast pace further exacerbates a high workload because it puts pressure on students to continuously stay on track with their studies. Eric writes: “So much is based on what you should have learned the day before, that the course is a bit like a race where if you falter and don’t immediately recover, you are sure to go down and be trampled.” and “There is no time to enjoy the success, no time to use those skills in order to discover more or dig deeper.”

Eric’s final verdict is not encouraging: “There are no sad faces on this, the last day of class. No one will miss this chore. No one will say to himself or herself, “I really enjoyed that,” or “that was an interesting learning experience.” Instead, people will congratulate themselves on having made it, will be happy with their “B” or their “C,” and will very soon forget anything pertaining to physics.”

Among the total of seven “second tier” students in the book who took college science course, all but one were among the top ten percent. Nonetheless, only two of the seven would continue in science if they had a choice. The main reason is likely the combination of the following three characteristics with which Eric describes his introductory physics course: “1) difficult to get a good grade; 2) time consuming; or 3) boring, dull, or simply not fun”.

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 26 MAY – 1 JUNE

Attending a scientific symposium

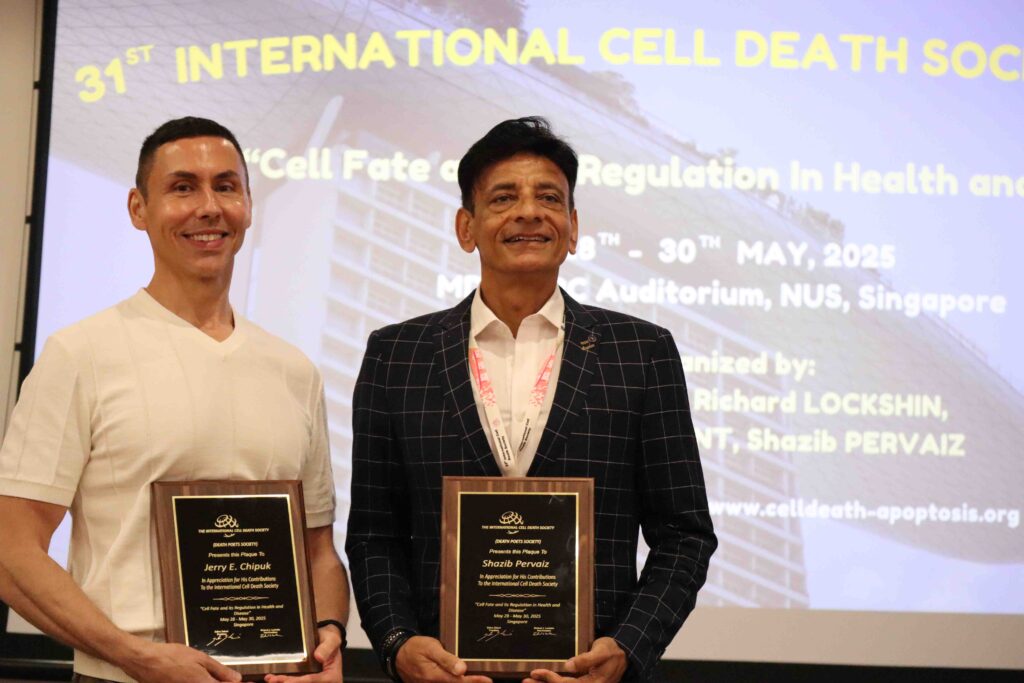

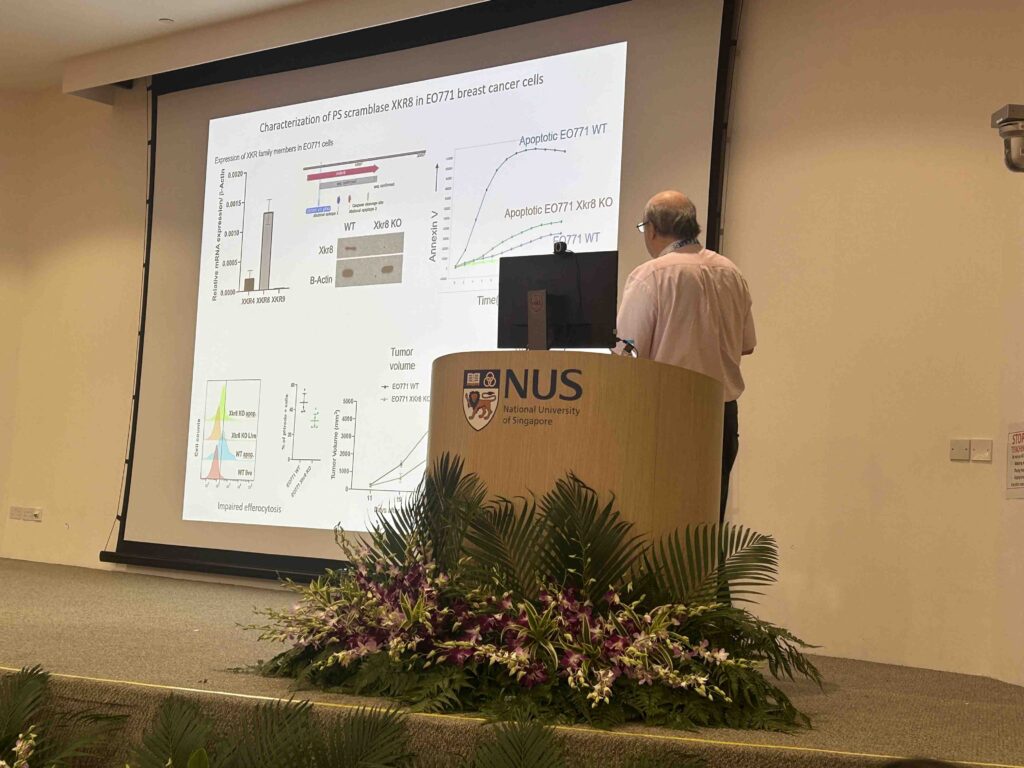

This week I attended a three day long scientitic symposium with my undergraduate student Kester, the 31st International Cell Death Society Annual Meeting, held at NUS School of Medicine. The theme of the conference was “Cell Fate and its Regulation in Health and Disease”.

Our NUS staff running group member Shazib was one of the main organisers of the symposium and also received the International Cell Death Society life time achievement award on the first day of the conference!

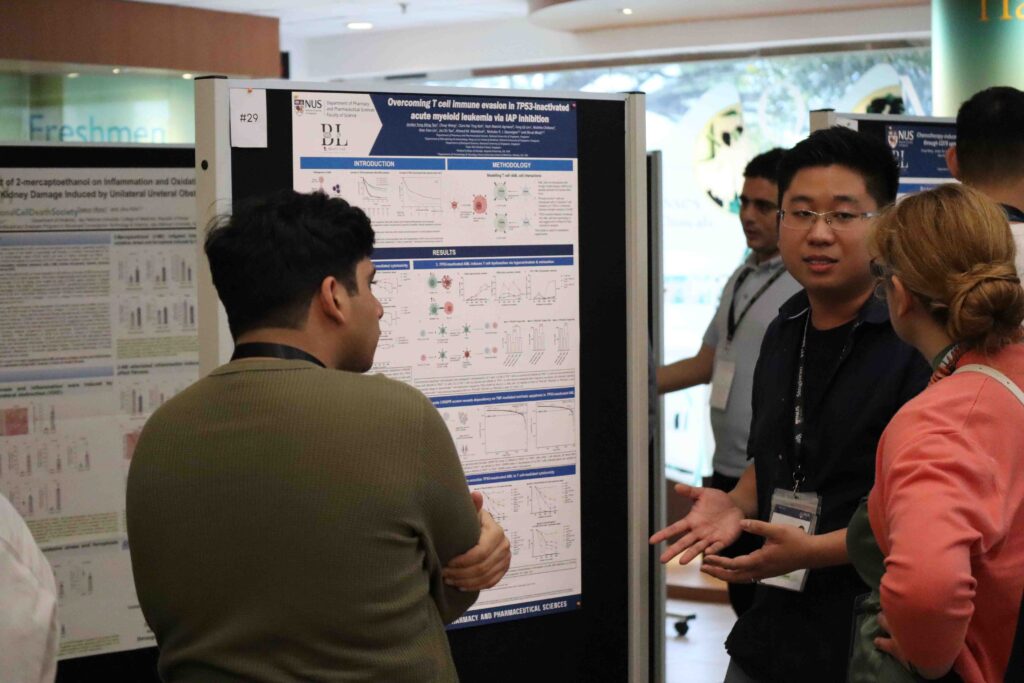

And here is Kester (on the right) discussing with Yash (second from right) the poster that Yash presented. Yash was also my student from last semester’s Cell Bio course.

All in all it I had a great time spending three days listening to many exciting scientific talks!

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 19 – 25 MAY

My ChatGPT assignment

One of my Cell Biology group assignments this past semester was based on a podcast I discussed previously, in which the host asked a real writer (the author Curtis Sittenfeld) and ChatGPT to write a story. The story had to include a number of words that were included in the prompt. The listeners could then test themselves whether they could tell which story was written by a human and which by AI.

I gave this assignment to my 45 student groups, letting the students listen to the two stories and then asking each group to discuss which script was written by a human and which was not and to justify their decision.

This does not seem like a typical Cell Biology assignment. Nonetheless, I believe it is relevant because when engaging with cell biology research in the real world, students likely will be using generative AI tools.

It turned out that 35 out of the 45 groups “guessed” correctly who the human writer was. However, what was much more impressive was the sophisticated reasoning that many of the student responses revealed.

Some students focussed on the writing technique, revealing in some cases extraordinary proficiency. One student group highlighted several techniques used by the human writer, including “parallel syntax” [a writing technique that employs similar grammatical constructions within a sentence or paragraph], “a flow that indicates authorial intent” and “foreshadowing”, where something that was said (or in the case of the story something that was not said) becomes significant later on. The student Zixuan continues …: “This is likely human intent that cannot come from a chatbot that predicts the next most likely word.”

It highlights something I have not really recognised – predicting the most likely next word in a sequence makes it difficult for a chatbot to develop intent in creative writing and to produce elements of surprise.

Analysing the ChatGPT generated story, Zixuan continues her impressive analysis and writes: “With the second story, however, the characterisation of Lydia is very disconnected from the exposition [or the background information of the narrative]. Details about her life at the start (e.g. frequents the cafe, has a child, late husband) explains her “greyness” in life when compared to her friend, but this is separated by meaningless exposition. Pragmatism as a character trait in her flip flops is assumed and not explained, and is meant to link to the love interest, but this is also separated by other exposition. The lack of explicit connection indicates a lack of thought as to what the narrative is meant to suggest.”

Another amazing comment was made by another student, who observed “The first story got the math correct which usually does not happen in non-reasoning AI models, the biker guy was born in 1971 and was 53 years old which is around 2024.” The same student also noted that the ChatGPT response was very conservative with regards to referencing interpersonal relationships, revealing a programmed avoidance of any kind of ambiguous references to love. Again, the students did not know which story was written by whom. As such, the ability to observe and note such subtleties is really amazing and suggests types of intelligence that we normally never test in science teaching.

It makes me recall another student in last semester’s course, Winston, who asked me some really amazing questions after classes, which I had never thought about.

When I was in high school, I remember taking a special physics course where during our first class one of the students asked the teacher a question. The teacher responded by saying that the question was so good that if this were a normal class, he would award the student with a “1” (which is in the German school system the equivalent of an “A”).

Winston got an A+ in the course, even without awarding him extra marks for his questions. But what the comments and questions by the two students illustrate is that I normally do not do enough to promote, encourage and award skills of observing details and asking good questions.

There were various other interesting clues that students recognised:

With regards to the human-written story, there was a rather broad consensus that it expressed more emotions, more informal expressions and “slang” (like ‘oh crap’, ‘I SWEARR!!!”) as well as more phrases that were unexpected and that “deeply connect with human readers”. The students concluded that these are things that AI generated texts usually do not contain.

I was particularly impressed that two groups pointed out references to the recent TV show Severance, which apparently gained popularity very recently and hence, ChatGPT was unlikely to have encountered information about the show during its training.

For the story written by ChatGPT, the students found even more indicators that gave the non-human origin away:

With regards to the language, the students perceived it to be more formal, too perfect and excessively descriptive. The word choice was not as simple as in the human story and instead, ChatGPT used more bombastic words. Several groups pointed out the flowery language as a common feature of AI generated creative writing.

With regards to the writing style, one group (group 16) noted that whereas the “first story has a specific style, the second story has a very generic narrative format. This shows that AI is leveraging on the existing database of narrative stories “

Another group (group 47) wrote: “… the second story feels highly formulaic and somewhat stiff. Although we can see the use of various rhetorical devices like metaphors and parallelism to enhance literary beauty, the lack of soul and the overly mechanical piling of words suggest that it is generated by AI trying to imitate real writers’ content by extracting so-called templates or formulas.”

There were also some specific tell tale signs that the students noted and that I missed completely: ChatGPT tends to use the rule of 3. Based on the sentence structure, the ChatGPT story seemed to use a lot of em dashes (long dashes), typical of AI generated text. Group 21 noted “… the entire setting is so cliche, … it is in third-person, the [prompted] word ‘flip-flops’ was repeated so many times – as if to match very close to the prompt given.”

Finally, Group 22 wrote this (which also goes to show how students make use of technology in ways that most professors are unaware of): “Only a writer, and not chatbot, would be able to capture such raw human emotions and strange experiences. Furthermore, the first story is more spontaneous, with random imagery and word choice that caught our attention more compared to the second story which really all we remembered was Lydia. The second story is too smooth and easy to understand if we actually paid attention (we transcribed using a dictation feature on OneNote!), and had very long sentences which are used in most basic stories.”

What it all goes to show is that students are really very AI literate!

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 12 – 18 MAY

Addictions: Searching for excitement

In my recent post on setting my priority I mentioned the importance of not wasting time on activities and thoughts that do not contribute to pursuing my priority or to improving my happiness. As such, I have been reading and thinking a lot about addictive behaviours, including reading a great book by Seana Smith “Going under”. In her book, Seana Smith describes how she grew up with an alcohol-dependent father, how she became alcohol dependent herself and how she overcame her dependency.

As a result of all this reading, I have come to a number of insights:

Firstly, the reason why we do addictive things is not just because they have become a habit, but because they are truly exciting and pleasurable to us.

Secondly, people have different addictive tendencies. This may in part be genetic (?). I do not drink any alcohol, but even if I did, I am confident that I would not become dependent on alcohol. I do not enjoy the taste and I have never had an alcohol-induced exhilarating experience that makes me want to drink.

I believe that our addictive tendencies are, at least to some extent, determined by our adolescent experiences. The author Seana Smith started drinking alcohol as a University student, and this practice was linked in her brain to many exciting experiences. I started collecting records in my teens and continued to do so in my twenties, and I have lots of exciting memories of finding record stores all over the world.

Of course, we can pick up addictive habits at any stage during our lives. But it appears that the longer we experience a habit, the more difficult it becomes to change this habit.

The third insight is that it is difficult, probably impossible, to “control” an additive tendency or to pursue an addictive habit in moderation. Seanna Smith writes at the end of her book:

“Stopping completely is a piece of cake compared to the mental torture of attempting to moderate when you just can’t. Make your life better, make it easier. Set yourself free.“

When we engage with our addictive habit, our brain experiences either pleasure, which drives us to continue, or a lack of anticipated pleasure. Because of our memory of pleasurable experiences when pursuing the habit, we try to find pleasure at all cost.

For example, when I used to visit “physical” record stores a lot, there were two possible scenarios. The first is that there were loads of interesting records, which got me excited and made me keep on searching to ensure I will not miss anything. Alternatively, there were no interesting records, as a results of which I felt the urge to keep on searching until I find at least one interesting record, to satisfy my search for pleasure and excitement. I personally feel that this is true for any addictive habit, even the consumption of alcohol.

This brings me to my fourth and final insight. If we cannot stop once we have started, we need to find ways to not start in the first place.

As such, an important question is why do we start pursuing an addictive habit in the first place, against better knowledge that we actually do not want to engage with this habit and that we will likely regret our action afterwards. The reason is of course that our brain seeks novelties, unexpected experiences and exciting discoveries. This makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint in a world where there aren’t many novelties. But it is not well-suited in a world where there are novelties in abundance.

This makes it clear that it is critical to address the desire to have an exciting experience. There are various commonly recommended approaches to curb this desire. Being able to maintain abstinence for extended periods can help, because it makes our brain “forget” the pleasurable experience. To achieve abstinence, we can implement practical measures, such as ways to introduce accountability.

Another approach that I have previously discussed is Rational-Emotive Therapy/Addictive voice recognition technique, where we dissociate ourselves from our “addictive voice” and make a commitment to life-long abstinence, consequently not even entertaining the possibility of ever falling back onto our addictive habit.

However, many people are not willing to make a life-long commitment, for fear that they will lose their pleasurable experience and that there will be nothing to look forward to. This is because it is difficult to imagine that a habit will one day become unimportant to us, even though probably everyone has lost interest in some things that we used to be very passionate about. Another danger when making a life-long commitment to abstinence is that people develop new addictive habits instead.

There is also the substitution strategy, where people find other things to replace an addicitve habit. In the case of alcohol dependency this could be non-alcoholic drinks. We could find other activities that we are really excited about, so that the temptation to waste time with an addictive habit becomes less likely.

However, these “solutions” do not get to the real issue that in the ideal scenario, I would like to be able to make the free decision to not pursue things that I know do not contribute to my well-being and happiness. To achieve this, we have to find ways to not start an addictive activity in the first place, as discussed above.

As such, I believe that the best strategy is to convince ourselves that an addictive habit is not truly as exciting as it may seem.

After giving this much thought, I feel that one possible approach is to focus on what I have instead of what I want and to change the emphasis in my life from exploring and discovering novelties to enjoying life.

The idea that life is not principally about discovering novel things and experiencing makes sense to me because there is no end in doing so. Discovering something always leads to new questions and the urge to discover more. Because we can never discover everything, it is difficult to gain satisfaction from exploring new things. I believe that life is really about living and enjoying life, and most people (at least in our society) have everything that they need to achieve that. Of course, we need to explore some novel things to make an impact in our sphere of influence, but we do not need to do it to live a happy life.

I have in the past decided, consciously or unconsciously, to not spend time and thoughts on things that I could be obsessed about, such as buying new audio equipment or sports related items, such as buying the latest running shoes or getting a new bicycle, because none of these things would fundamentally change my experience. This has helped me greatly in not getting distracted by things that are not important. As such, I will try to expand this mindset to all areas of my life.

For instance, I have compiled a long list of books that I want to read. If this was a list of research or education papers that I want to read to come up with new research ideas or teaching strategies, then this would make sense. But the book list is based on a “fear of missing out”, worrying that I may miss out on reading potentially amazing books. The truth is that no matter how long my list is, it will always only include a fraction of what I could truly discover. The logical conclusion then is to not compile ever longer lists, but to drop the idea of compiling a list altogether. There is no doubt that I will never run out of interesting things to read, whether I compile this list or not.

The purpose of reading is to enjoy reading, not to read every possibly exciting book there is.

The purpose of living is to live happily, not to live the best possible life.

And so when facing new exciting, potentially addictive, opportunities, we can say to ourselves that there is no point in pursuing ever more exciting possibilities because what we have is already enough.

So finally, how did the author Seanna Smith, pictured above, manage to overcome her alcohol dependency?

As mentioned above, she could not bear the thought of never drinking alcohol again, and hence was unable to commit to “never drink again”.

Instead, she set the goal to stay abstinent for one month. She also discovered non-alcoholic drinks that she really enjoyed.

After some time a shift happened for her, where something she could not imagine previously became possible – the thought of never drinking again. This turned into a plan and eventually into reality.

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 5 – 11 MAY

My plans

The semester is over and I feel excited about the new gained freedom. As I am planning how I want to spend my time in the coming months, I want to be careful to not pursue too many things. As such, I am re-reading (or reading it for the first time, I am not so sure…) Greg McKeown’s “Essentialism – The disciplined pursuit of less“, in which he discusses the importance of setting priorities in our lives.

To be more accurate, according to McKeown I should be setting the singular priority. As the author emphasizes, according to the true meaning of the word, there can only be one priority. Yet, many people, including myself, tend to pursue priority No.1, priority No.2, No.3 etc. As a result, none of these things becomes a real priority.

That said, setting a priority does not mean that we do not do other things. But it means that we are willing to give up other things in favour of our priority when necessary.

When trying think about how I want to spend my time in the months to come, in addition to setting a priority, there are a number of other considerations.

These include firstly how I can incorporate into my daily life activities that are important for me to live happily. This includes planning time to do things that I enjoy and look forward to, including spending time outdoors, listening to music and reading, and that are important for my happiness, such as doing exercise and sleeping enough.

Yet another challenge is to minimise time spent on distractions in the form of unhelpful habits and unwanted thoughts that neither help me in achieving my priority nor in feeling happier.

I will leave the distractions for another post, and focus here on my priority. The concept of setting a priority echoes with me because these days, after the busyness of the semester is finally over, I realise how short my days are, especially when there are so many things I would like to do.

Furthermore, it is true that without dedication towards one specific thing it is difficult to make true progress. A good example is research, where it is easy to have an idea, but hard to test this idea and even harder to complete all experiments necessary to publish an idea and convince others of it.

When thinking about priorities that I could focus on in the months to come, a number of things come to my mind.

Firstly, there is my research, which I was forced to neglect over the past few months. There is, however, the constraint that our resources for research are very limited.

Secondly, there is my stated goal of achieving accomplishments this year, including establishing a creator LinkedIn profile where I share my teaching experiences.

I could also prioritise to improve my teaching or to become an athletics coach. Finally, I could focus on personal improvement, such as gaining public speaking or writing skills.

That makes five potential priorities, when I can only have one. How to decide on the priority?

Perhaps I could try to ask myself a number of questions:

What do I feel inspired by? The true answer is “all”.

What gives me joy and satisfaction? The answer to this is “all” as well.

What would have the most impact? Probably improving my teaching, research and athletics coaching. The reason is that for all of these activities I can make a direct impact on people, whether it is my students in the classroom, my students in the lab or people becoming excited about exercise.

What will be important for my future, especially after I retire? Most likely accomplishments, athletics coaching, and personal improvements, because all of these may open up new opportunities.

What can I do later? Given that I am only a few years years from retirement, the only thing that I could potentially put off for a bit is personal improvement.

Another question to ask myself is what will be of importance to me when I eventually will be looking back on my life? It will unlikely to be research discoveries. It will also less likely be people who I made a difference to because in most cases the impact I have is only temporary.

What I think will be important, besides experiences and times I spent alone and with my family, are personal achievements that only I could have done – teaching Cell Biology in ways that nobody else has done, organising the annual Young Scientists Symposium in a way that it has become a meaningful event, establishing an NUS staff running community, perhaps also publishing a book.

However, thinking about all these questions is not really giving me an answer. So why am I thinking about setting a priority in the first place?

The true reason is that I do not want to feel stressed and not be able to have enough time for myself.

Hence, having enough time for myself should perhaps be my priority. I can still pursue all the other things, but they should not be in the way of meeting this priority.

Life is short, and as I have read somewhere recently, people often realise too late that they have not lived enough. This usually happens when their health is failing and they realise that they no longer can do all the things they would like to or wanted to do. It goes to show how important it is to do the things that are important for us personally now.

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 28 APRIL – 4 MAY

Designing an AI safe exam

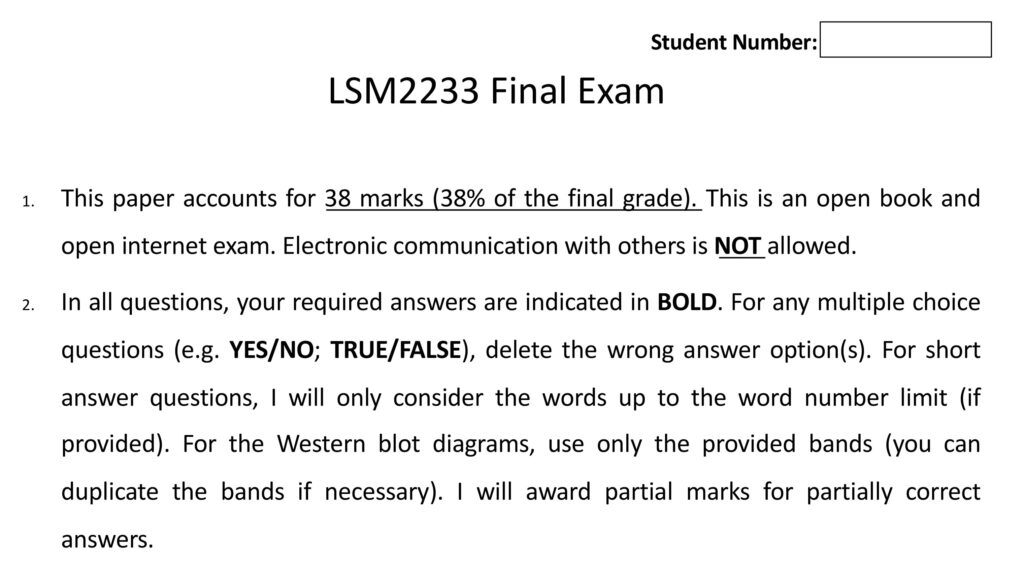

Last week was the week where my 136 students took my Cell Biology final exam. After the experience of many technical difficulties in the mid-term test, I made the decision to make the final exam an open book and open internet assessment. While this would address potential problems with blocking the internet and password-encrypted files, it meant that I was taking a significant risk as to whether I could come up with an AI safe set of exam questions.

My decision to conduct an open book and open internet exam served three purposes.

Firstly, I wanted to avoid the above-mentioned technical difficulties. Indeed, the exam proved to be very easy to conduct. All I had to do was publish my exam file at the beginning of the exam. I could even amend my exam questions literally until the last minute.

As a result, the exam was free of stress for me. Likewise, the students looked more relaxed. While there was still the usual exam related stress, the students did not have to fear technical problems and likely felt assured that they could rely on the open internet. I felt that this was the atmosphere that I would envision for a real world like exam. Indeed, conducting an exam that mimics the situation that students encounter in the real world was the second reason why I decided to allow an open internet.

The final reason for allowing free online access was to help students to learn how to use generative AI responsibly and make their own, wise choices about when and when not to use chatbots and how to use them. I also wanted to make the exam consistent with the message that I was trying to convey to the students throughout the semester: Generative AI tools can be helpful for certain practical applications, but we should avoid handing over things that make us human and let is enjoy our work and lives. Teaching students to make these choices can only be achieved if we offer them these choices and let them experience what the consequences of choosing different approaches are.

Our exam venue

What did I have to do in order to make my exam “AI safe”?

Firstly, we had to find a suitable venue that allowed us to invigilate the students properly as well as solicit additional invigilators in order to ensure that students do not communicate with each other using their laptops. I also told the students that while they are allowed to use ChatGPT or other chatbots, they are not supposed to paste the whole paper or individual questions into the chatbots.

Of course, students not pasting questions into ChatGPT was difficult to enforce and hence I also had to design suitable questions that could not be answered by ChatGPT and test the questions beforehand. Besides not giving students too much time during the exam, there were two strategies that helped to make the questions AI safe. One was including many questions that involved drawing of diagrams. The other was that half of the questions were based on a research paper, which the students were given a few weeks before the exam. Answering these questions really required very detailed and specialised knowledge that ChatGPT did not have. A third approach was to include in some of my questions the answer proposed by ChatGPT and let students evaluate whether the chatbot response made sense and justify their answer. As a result, as one student attested, ChatGPT was unable to provide much help in answering my questions.

One question is whether this approach is sustainable, given that AI will improve, and likely in an exponential manner. I think that in the near future the answer is (hopefully) yes, in particular if I continue to focus on problems that require detailed prior knowledge, as is the case when answering questions about data figures in a research paper that the students need to study before the exam. As such, I am considering to only use research paper based questions in my exams in the future. This will probably require that I assign the students two papers before the exam.

How did the exam go?

Reassuringly, there were no problems related to question ambiguity or lack of clarity, which is always a big relief.

As always, the exam was difficult, with an average of only about 50%. One third of the students could not finish, even though I always try to predict generously how much time students would need to answer the questions. That said, there are two limitations. Firstly, knowing the answers and not being a student makes it difficult for me to predict how long a student who does not know the answers may need. Secondly, I assume that students have a certain amount of knowledge and do not spend time looking up basic information. As such, I suspect that many of the students who did not finish all questions were either not well-prepared or did not plan their time well.

This again brings me to the recurring question of whether I should make my tests and exams easier. However, every time I consider this, I end up with the same considerations and conclusions:

1. Scientific research is difficult, so why give students the impression that it is easy. As such, making questions too easy can give students a false sense of mastery. It may also make them disappointed that despite doing “well” in the exam, they do not end up with the grade they predicted. In fact, by making the exam difficult, students will be much more likely surprised that their grade ends up better than they had expected.

2. Giving students more time will not necessarily allow them to think the questions through more thoroughly. Instead, many students are likely to spend more time searching their notes or consulting ChatGPT.

3. Difficult questions are ultimately the best way to determine how much students have understood in the course and how well they are able to apply what they have learned.

So all in all, my Cell Biology final exam was a success. It proved to be stress free, fair and although difficult, able to assess how much students have learned.

HIGHLIGHTS FOR WEEK OF 21 – 27 APRIL

The age of screen culture

While every time during my busy teaching semester I try to maintain my usual daily schedule, towards the end of the semester this invariably fails. The end of the semester usually means that I literally give up everything else because my teaching-related commitments have become so demanding. And this semester has been no exception.

The problem with this is not only that I do not have time to do things that are fun. It also means that I stop truly living. I stop being a person who enjoys learning, creating, coming up with new ideas and finding solutions to problems. Instead, I become a person who only focusses on meeting all the deadlines.

I have no doubt that the same is also true for students, who when facing all the stress of the end of the semester turn to ChatGPT or Deepseek to complete their assignments and try to find temporary “relief” by spending time on their screens because there is no time for meaningful pursuits.

However, the use of chatbots as an easy solution and the lack of true intellectual engagement are contrary to the real purpose of University education, which is to prepare students for their future. This is exemplified by two interesting articles that I read recently.

The first dealt with how generative AI use can undermine the development of metacognitive skills.

Metacognition involves skills that go beyond being able to just carry out a task mechanically. Instead, it entails true understanding of a process, finding of individual solutions, being able to spot errors and fix them and knowing when to check for inconsistencies. The process of gaining metacognitive skills involves planning work independently, observing and reflecting on why a process has failed, asking questions and learning from mistakes.

In a recent article, entitled “The Widening Gap: The Benefits and Harms of Generative AI for Novice Programmers“, Prather et al. examined novice students solving programming problems with the aid of generative AI tools. In their study, the authors monitored the students during numerous coding lab sessions through observation, interviews and eye tracking.

The study came to three main conclusions:

Firstly, the authors found that students who possessed well-developed metacognitive skills benefited from using generative AI tools to complete the coding assignment faster. While using AI tools such as CoPilot and ChatGPT, they were able to ignore unhelpful or incorrect code suggestions. They were selective in terms of which suggestions they accepted and which not and often opted to think through problems on their own.

In contrast, students who lacked metacognitive skills did not benefit from using the generative AI tools. They accepted suggestion by the CoPilot AI tool more readily, and often realised later that these suggestion were unhelpful, prompting them to start all over. Instead, these students completed the assignment with an illusion of competence. In one example, the authors noted that based on a student’s comment, he or she “seemed to think that ChatGPT had augmented their critical thinking rather than replaced it, but the data above contradicts that.”

Finally, and possibly most importantly, for neither of the groups did using the generative AI tools help the students to develop or improve their metacognitive thinking skills.

In short, while AI tools did help some (but not all) students to accomplish tasks, it did not help with the learning.

This leads me to conclude that there are really only two reason to use generative AI tools in my own teaching.

One is to familiarise students with how to use specific AI tools effectively. This requires that we as teachers first learn how to use specific tools effectively ourselves. Otherwise, we are unable to help students to develop the skills, set suitable assessments and evaluate student output.

The second reason is to help students to develop metacognitive skills by designing exercises that evaluate AI tool output. This is something that I have focussed on in scientific writing and in research design tasks. And I will continue to incorporate these exercises into my teaching.

The second article that really inspired me is David Brooks’ column in the New York Times “Producing Something This Stupid Is the Achievement of a Lifetime“, in which he is referring to Donald Trump’s tariff policy.

In his article, David Brooks makes two important points: Firstly, reading, thinking and learning to overcome difficulties is important to future success. Secondly, in our current times, these things are being devalued, because people believe that we do not need these skills anymore. The consequences are arrogance, an inability to detect flaws in our thinking and ill-informed decisions even by people that hold position of great power.