Peer Instruction using Learning Catalytics

November 2021

Below is a blog article that I wrote for the NUS Teaching Connections site.

One year ago, in August 2020, I was fortunate enough to secure a slot in a webinar by Harvard physicist and pedagogist Eric Mazur (Mazur, 2020). The experience fundamentally changed my view of online teaching and made me realise how exciting Zoom lectures can be. Even though this webinar started on a Saturday morning at 4am Singapore time, falling asleep did not even cross my mind.

I used to consider online teaching inherently less engaging than teaching in person. However, this perception changed when I experienced peer instruction as a “student” being placed into a Zoom breakout room and discussing problems with peers. In peer instruction (Zhang et al., 2017), students are challenged with problem-based questions, which they first try to answer individually. Subsequently, they join together in groups, discuss their answer choices from the individual round and try to come up with a joint answer, which they then submit. This works really well in an online setting, largely thanks to a web-based learning platform called Learning Catalytics.

In the webinar, we attendees first answered a set of questions individually in the web-based Learning Catalytics platform. I then joined a breakout room with three other lecturers from different parts of the world. Being able to see what everyone else had answered in the individual round on the Learning Catalytics interface, we started discussing immediately. When we submitted our joint answer and it turned out to be correct, we immediately felt connected. This activity felt so different from many breakout room discussions that I previously experienced where students are not really motivated to participate and engage.

The workshop demonstrated to me the importance of having first thought about a problem on our own before discussing with our peers. As a result of the prior engagement with the problem, I was more motivated to discuss my reasoning with others and be better prepared to defend my choice of answer.

After attending the workshop, I was determined to use Learning Catalytics in my Year 2 undergraduate course LSM2233 “Cell Biology”. I was lucky that my Department sponsored the purchase of licenses1 and I made full use of it, by literally conducting Learning Catalytics-based team activities in every lecture.

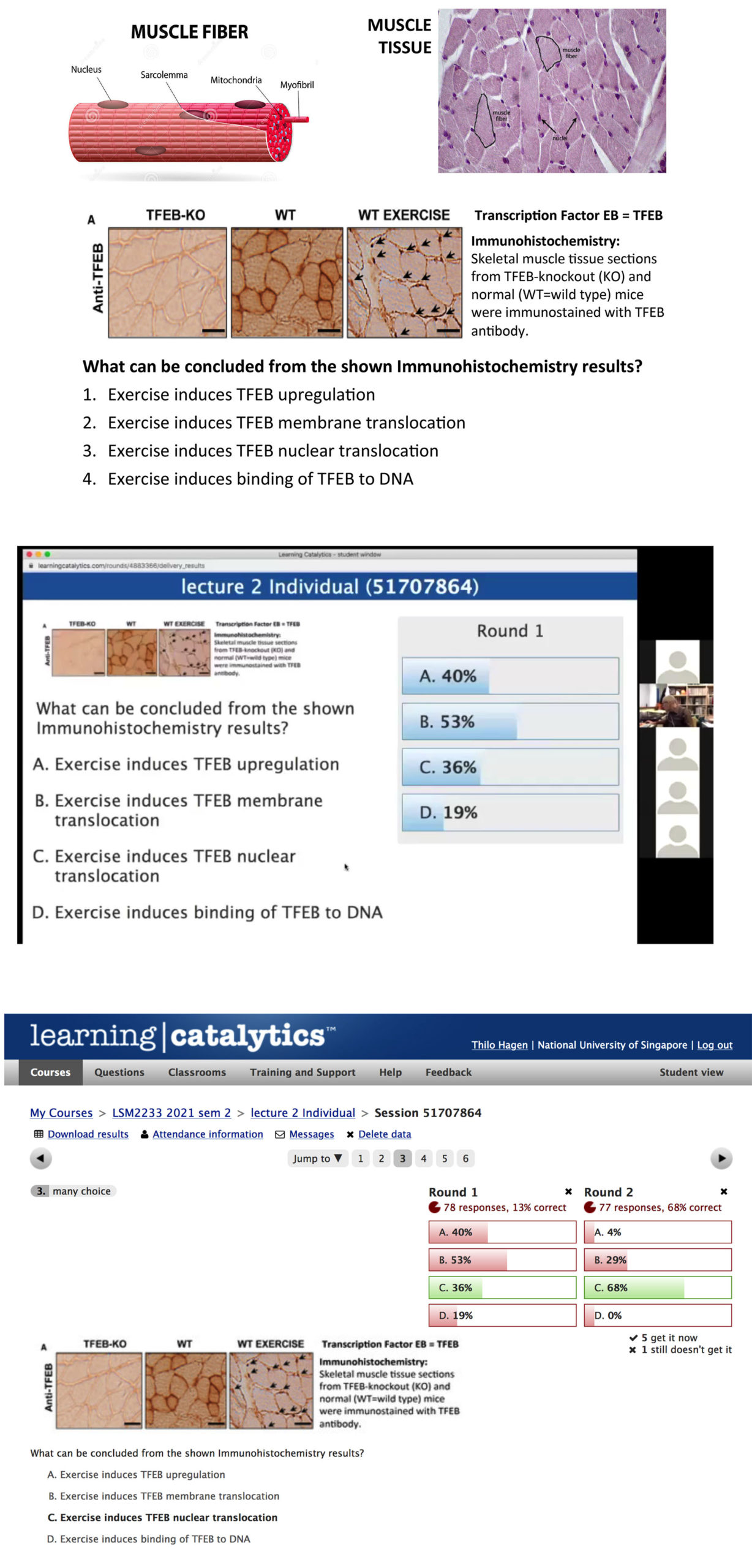

In one of my two lecture slots, I used individual questions, which were delivered twice. The students first answered the question on their own before being placed into breakout rooms, in which they discussed the question with their peers and submitted an answer again. An example of this activity is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Screenshots of a Learning Catalytics sample question:

Top panel: Original question posed during the lecture

Middle panel: Students access Learning Catalytics and answer the question individually. At the end of the individual round, the student votes are shown to the students without revealing the correct answer. Students then enter zoom breakout rooms, where they discuss and re-answer the same question.

Bottom panel: Instructor view of the session in Learning Catalytics. The instructor can see the students votes from the individual round (Round 1) and the team round (Round 2) in real time. A marked increase in correct answers was observed after the team round.

In my other lecture slot, I performed in class team-based assessments in the format described above. I found the team-based assessments especially useful, because these types of assessments are much less stressful compared to normal assessments. Furthermore, the students really learned while doing the assessment, as immediate feedback was provided.

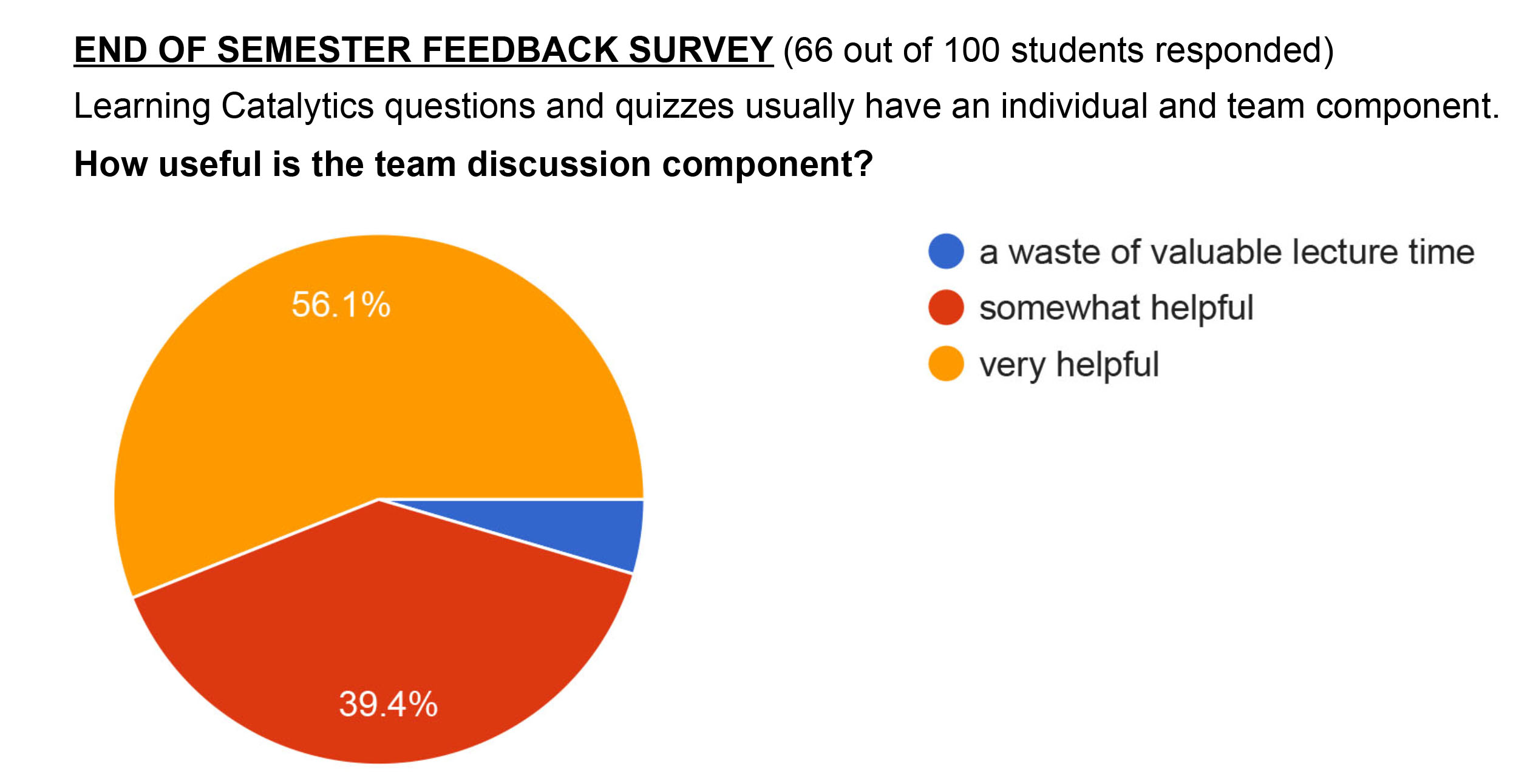

Based on my end-of-semester survey results, the vast majority of students indeed felt that the team discussions were helpful to them (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Students’ responses to the question “How useful is the team discussion component?”

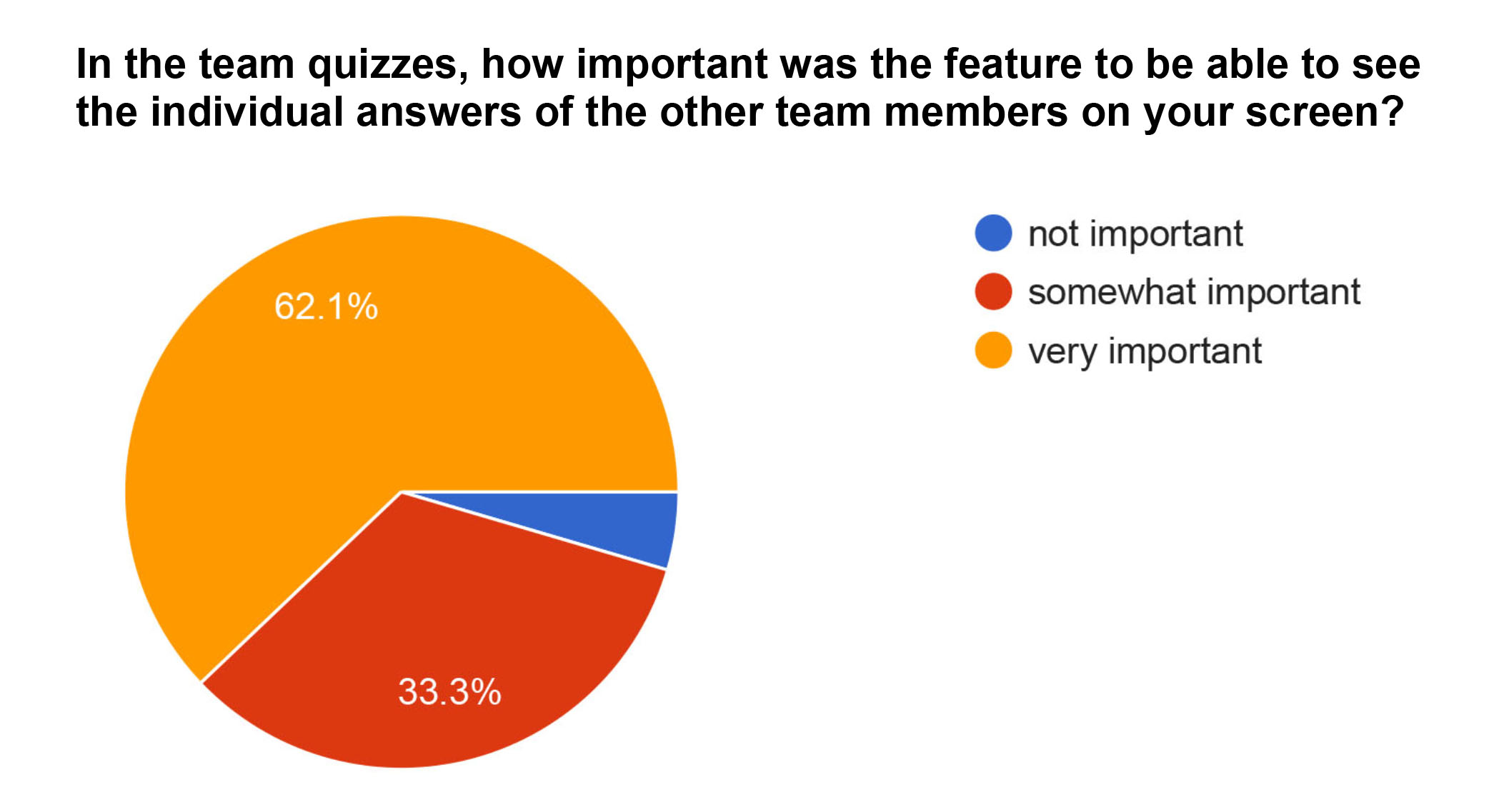

To conduct these activities, Learning Catalytics proved really helpful, as the courseware was specifically designed for peer instruction and allows the instructor to deliver questions multiple times. Furthermore, during the team discussion, students can see on their screens (through the Learning Catalytics interface) what the other students have answered in the individual round. This feature is really important (see Figure 3) because it allows students to start discussing the problem immediately. It also ensures that everyone’s opinion contributes to the discussion, even the opinion of students who normally stay passive.

Figure 3. Students’ responses to the question “In the team quizzes, how important was the feature to be able to see the individual answers of the other team members on your screen?”

Secondly, Learning Catalytics provides immediate feedback and students can attempt a question multiple times, a feature that proved really helpful and popular with students (see Figure 4). After three failed attempts, the correct answer, along with an explanation, is provided, ensuring that learning can happen for all students.

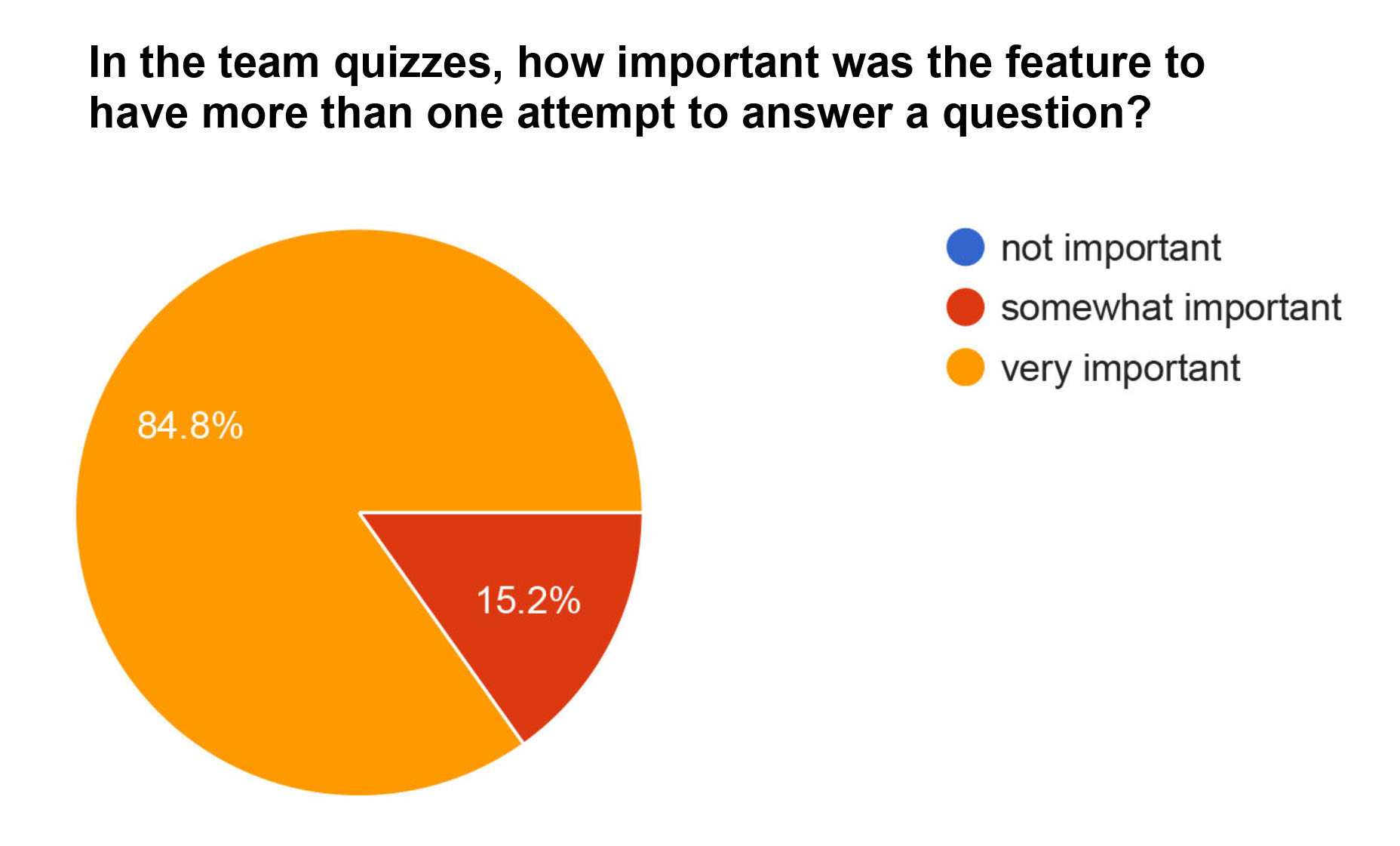

Figure 4. Students’ responses to the question “In the team quizzes, how important was the feature to have more than one attempt to answer a question?”

Using peer instruction and Learning Catalytics has not only resulted in my best student feedback scores, it has also made my online module more engaging than my live classes in the past.

Getting familiar with the ins and outs of the Learning Catalytics courseware does take some effort. However, the support team at Pearson has provided helpful and prompt feedback, which made it a less onerous process. From the students’ perspective, the most common concern was that the platform currently does not allow for the awarding of partial marks to partially correct answers. From a lecturer’s point of view, one concern is that importing the downloaded Learning Catalytics quiz results (in excel format) into the university’s learning management system LumiNUS requires some manual editing.

Notwithstanding these concerns, I look forward to continuing to use Learning Catalytics in all my undergraduate and postgraduate courses and to hopefully try out the platform soon in face-to-face classes!

Endnote

- The standard price for a license is 15 US dollars per student and the duration of the license is 6 months.

References

Mazur, E. (2020, Aug 14). Remote Teaching with Eric Mazur [Webinar].

Zhang P., Ding L., & Mazur, E. (2017). Peer Instruction in introductory physics: A method to bring about positive changes in students’ attitudes and beliefs. Physical Review. Physics Education Research 13(1), 010104.

And here is a webinar with practical demonstration on the use of Learning Catalytics in my classes.